When most folks think of Mustangs and/or wild horses, those roaming the western plains usually come to mind, or maybe the Chincoteague ponies. Many don’t realize that there are several herds of wild horses on the Atlantic shore. These herds are on Assateague Island (above and below the Maryland-Virginia state line); on Chincoteague, Virginia and the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge; on Carrituck Banks, North Carolina; on Ocracoke, North Carolina; on Shackleford Banks, Carrot Island, and Cedar Island, North Carolina; and on Cumberland Island, Georgia. Wild horses have lived on these barrier islands for hundreds of years, but their history, existence, ecological niche and impact on their habitats is often misunderstood and misinterpreted by lay people, government officials, and scholars.

Bonnie Gruenberg, a healthcare professional and lifelong equestrian, examines the controversial and often conflicting issues surrounding these wild horses in The Wild Horse Dilemma: Conflicts and Controversies of the East Coast Herds. She documents first hand their lives, social structure, and relationships with humans, based on a foundation of objectivity and scientific integrity. “My goal was to create a trusted resource that is useful to professionals yet intriguing to laypeople,” she said, “but my respect for and fascination with these horses shines through.”

Gruenberg spent two decades in the field observing these wild horses and human behavior toward them. She examined historical records and genetic studies, disseced folklore and journalism, and exposed many unexamined assumptions about them. She asked tough questions about them. Are these animals native or re-introduced exotic imports? Wild or feral? What might be gained by saving wild horses from extinction, and what might be lost if they died out? How did these horses come to exist on these particular lands?

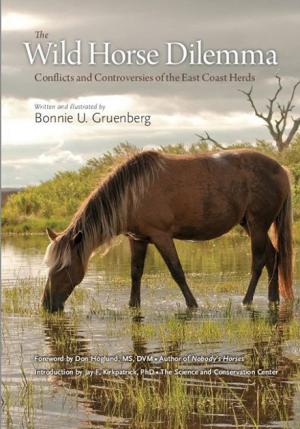

The Wild Horse Dilemmais an extensively researched and documented account of the history, genetics, social structure, lives, ecological impact, human attitudes toward these wild horses, and much more. She begins with examining the conflicting attitudes and controversial historical accounts of these wild, or feral? horses. How we define them often determines our attitudes toward them. She follows this opening chapter with a chapter on Mustang management and the political policy side of human behavior toward these horses. “To understand the conflicts affecting the … herds in the East, we should look carefully at passions aroused by, precedents set for, and assumptions made about the mostly larger, lower-profile herds in the West.” The rest of the book is a chapter on each of the east coast herds listed above and concludes with a chapter on the author’s commentary. Each chapter ends with multiple pages of references cited, and each chapter includes Bonnie’s amazing photographs of the horses from each particular herd. She writes: “…enigmatic is the pull wild horses have on our souls. We resonate with horses at a level much deeper than rationality. Many people who have never been close to a living horse identify with its power, grace, and independence and appreciate its beauty…” Then there are others who believe: “The horses shouldn’t be here at all! They aren’t native wildlife, and I don’t understand why the Park Service allows them to remain.”

Gruenberg delves in depth in these wandering bands of horses, describing their social structure, mating behavior – stallions’ behavior and mare’s receptivity, reproduction/fertility rates, infant mortality rates, bachelor bands of colts, and their longevity and the human induced factors that affect it. She informs the reader with her own observations, scientific research data, and information gleaned from government agencies charged with their management. She details the types of “birth control” measures used on Mustangs, their effectiveness or ineffectiveness, and the results in variation of herd size over time.

She informs about the ecological niche these horses occupy and their grazing impacts on the land. Included here are the human-made limitations on their grazing habits, such as fences, and the human development that brings changes in sand dunes, grasses, and the natural “migration” of sands along the shore. Conflicts between horses and humans occur as development encroaches on land for horses. Some encounters of wild horses with humans are rather humorous, and the show the intelligence and lack or fear in these animals as they raid camps for food or hold up traffic. There are also sad accounts of stress, injury and death to these horses in failed human attempts to “harness” them or “manage” them. She also documents the decades of the slaughter houses when horsemeat was a viable global commodity and Mustangs were regularly rounded up to feed the horsemeat processing plants.

“While some federal officials have supported the horses as free-roaming wildlife, others have tried to discredit them through intense disinformation campaigns,” labeling them as “non-native, feral, and exotic to justify removing them as pests and intruders,” she summarizes. “The future of the wild horse is dependent on a number of factors,” writes Jay Kirkpatrick, “and the largest single factor controlling the fate of wild horses anywhere will be public opinion.” Gruenberg believes “the American public cares passionately about the fate of wild horses, and the majority of us want to see them remain wild and independent.”

As comprehensive and detailed as the book is, it has two basic flaws. When one has as massive an amount of information as Gruenberg has, it is too tempting to want to include everything. The book would be a much better read with tighter editing. The chapters tend to ramble from one topic to the next, albeit related ones; there is repetition that could have been eliminated; and some of the minute details could have been eliminated while still making the basic point. One piece of advice I would give any writer: have skilled editors! Even a good story, if not well-told, will lose the reader’s interest. The other is the black and white photographs. While black and white photos have their place, these seem rather bland compared to her stunning color photos as seen on her websites.

For more information and photos, visit www.bonniegphoto.comor www.BonnieGruenberg.com

Bonnie Gruenberg, a healthcare professional and lifelong equestrian, examines the controversial and often conflicting issues surrounding these wild horses in The Wild Horse Dilemma: Conflicts and Controversies of the East Coast Herds. She documents first hand their lives, social structure, and relationships with humans, based on a foundation of objectivity and scientific integrity. “My goal was to create a trusted resource that is useful to professionals yet intriguing to laypeople,” she said, “but my respect for and fascination with these horses shines through.”

Gruenberg spent two decades in the field observing these wild horses and human behavior toward them. She examined historical records and genetic studies, disseced folklore and journalism, and exposed many unexamined assumptions about them. She asked tough questions about them. Are these animals native or re-introduced exotic imports? Wild or feral? What might be gained by saving wild horses from extinction, and what might be lost if they died out? How did these horses come to exist on these particular lands?

The Wild Horse Dilemmais an extensively researched and documented account of the history, genetics, social structure, lives, ecological impact, human attitudes toward these wild horses, and much more. She begins with examining the conflicting attitudes and controversial historical accounts of these wild, or feral? horses. How we define them often determines our attitudes toward them. She follows this opening chapter with a chapter on Mustang management and the political policy side of human behavior toward these horses. “To understand the conflicts affecting the … herds in the East, we should look carefully at passions aroused by, precedents set for, and assumptions made about the mostly larger, lower-profile herds in the West.” The rest of the book is a chapter on each of the east coast herds listed above and concludes with a chapter on the author’s commentary. Each chapter ends with multiple pages of references cited, and each chapter includes Bonnie’s amazing photographs of the horses from each particular herd. She writes: “…enigmatic is the pull wild horses have on our souls. We resonate with horses at a level much deeper than rationality. Many people who have never been close to a living horse identify with its power, grace, and independence and appreciate its beauty…” Then there are others who believe: “The horses shouldn’t be here at all! They aren’t native wildlife, and I don’t understand why the Park Service allows them to remain.”

Gruenberg delves in depth in these wandering bands of horses, describing their social structure, mating behavior – stallions’ behavior and mare’s receptivity, reproduction/fertility rates, infant mortality rates, bachelor bands of colts, and their longevity and the human induced factors that affect it. She informs the reader with her own observations, scientific research data, and information gleaned from government agencies charged with their management. She details the types of “birth control” measures used on Mustangs, their effectiveness or ineffectiveness, and the results in variation of herd size over time.

She informs about the ecological niche these horses occupy and their grazing impacts on the land. Included here are the human-made limitations on their grazing habits, such as fences, and the human development that brings changes in sand dunes, grasses, and the natural “migration” of sands along the shore. Conflicts between horses and humans occur as development encroaches on land for horses. Some encounters of wild horses with humans are rather humorous, and the show the intelligence and lack or fear in these animals as they raid camps for food or hold up traffic. There are also sad accounts of stress, injury and death to these horses in failed human attempts to “harness” them or “manage” them. She also documents the decades of the slaughter houses when horsemeat was a viable global commodity and Mustangs were regularly rounded up to feed the horsemeat processing plants.

“While some federal officials have supported the horses as free-roaming wildlife, others have tried to discredit them through intense disinformation campaigns,” labeling them as “non-native, feral, and exotic to justify removing them as pests and intruders,” she summarizes. “The future of the wild horse is dependent on a number of factors,” writes Jay Kirkpatrick, “and the largest single factor controlling the fate of wild horses anywhere will be public opinion.” Gruenberg believes “the American public cares passionately about the fate of wild horses, and the majority of us want to see them remain wild and independent.”

As comprehensive and detailed as the book is, it has two basic flaws. When one has as massive an amount of information as Gruenberg has, it is too tempting to want to include everything. The book would be a much better read with tighter editing. The chapters tend to ramble from one topic to the next, albeit related ones; there is repetition that could have been eliminated; and some of the minute details could have been eliminated while still making the basic point. One piece of advice I would give any writer: have skilled editors! Even a good story, if not well-told, will lose the reader’s interest. The other is the black and white photographs. While black and white photos have their place, these seem rather bland compared to her stunning color photos as seen on her websites.

For more information and photos, visit www.bonniegphoto.comor www.BonnieGruenberg.com