By Nancy Brannon, Ph.D.

Usually one sees horse people at Ames Plantation, near Grand Junction, Tenn., in December, January, and February, riding horseback in Field Trials, following champion bird dogs. But horse people and field trailers are interested in Ames history, too. And summer is the time to get updates on the archeological research at Ames.

On Saturday August 7, 2021 members of the Ames Historical Society were guests at the archaeology field day at Ames Plantation to learn the latest news from Dr. Kimberly Kasper of Rhodes College about their research at the Cedar Grove Plantation site. The group met at Bryan Hall to hear a presentation from Dr. Kasper and then to tour the recent “dig” site. This summer’s field school began on July 26 and ran for three weeks. Jamie Evans, Cultural Resources Manager at Ames, remarked, “We value our cooperative program with Rhodes College greatly. The field school allows for the recovery of a part of our history that would be impossible otherwise.”

The Ames land base is tied to prehistoric Native American towns and to people who tilled the land in later centuries. Dr. Kasper explained that while traditional “plantation archeology” focused on the owners of the plantation, that view has broadened and the Rhodes project focuses on the lives of the slaves.

Dr. Kasper’s presentation explained how archaeology is relevant in today’s world and connects the past to the present. Archaeology research can help bring more knowledge to understand how the past informs the present.

The basic theme of Rhodes’ research at Ames is Food Inequality, comparing plantation slave lifeways through archaeology with the current Memphis foodscape. The goal is to examine historical connections from the past to present food ways in order to provide solutions to the current health, socio-economic, food-based problems. Data on the current Memphis foodscape come from the Food Advisory Council, Heritage Garden, and OPCFM – the Overton Park Community Farmer’s Market.

To understand the lives of African Americans and their experiences through time and space in the south, this archaeology project utilizes historical documents and community outreach to supplement the archeology field school. Their current site of excavation is the former Cedar Grove Plantation, whose former headquarters is now the Ames Manor House.

Researchers collect oral histories from descendants of slaves still living in the area. Dwight Fryer, a descendant of slaves on the Ames land base, has provided a wealth of information to the Rhodes group, as he has done extensive research on his own family. They peruse documentary records such as slave narratives from the WPA and data from slave related archival documents and Census records on approximately 27 plantations. And the field school examines materials discovered in the “digs” at the site of former plantations on Ames property.

Their first “dig” was at Woodstock Plantation owned by Beverly Holcombe, who enslaved 42 African-Americans in the 1830s and 40s on what is today’s Ames landscape. Their second subject was the Fanny Dickins plantation, where 40 African-Americans were enslaved on property she owned from1841-1853. The current site is the larger, former Cedar Grove plantation, owned by John W. Jones from1827-1879, who owned 248 slaves, as per the 1850 slave schedule. The former slave quarters were located near where the Mule Barn sits now, and researchers expect remnants of more houses may be located to the east of their current “dig.”

Evans wrote in his quarterly newsletter that “we initially learned of the location of the quarters through an 1864 Civil War map, which indicated the cluster of houses just east of what, at that time, was the Cedar Grove manor house of John W. Jones (now the Ames Manor house). Jones was one of the most affluent planters in the region with over 4,000 acres of land, which was home to hundreds of enslaved African-Americans between 1826 and 1863.”

Evans has amassed a large collection of documentary records about the Ames Plantation, including land deeds, land entries, and slave transactions, much of which has been digitized and put on a searchable database at the website, www.amesplantation.org. Soon his team of volunteers will be adding personal letters, Bible records, court documents, newspaper articles, and more.

In her presentation, Dr. Kasper reported “what we have learned so far” from the documentary record.

· Seven of the 23 slave owners were female plantation owners

· 51% of the 674 enslaved individuals were age 15 or younger

· 40% of the enslaved individuals were between the ages of 16 and 40

· 12% of the slaves were over the age of 40

· 49% of the slaves were female and 51% were male

· 25% of the enslavers owned mulatto slaves (when mulattos were present they only comprised 10% of the population)

Dr. Kasper talked about how the slavery system was tied to commodity crops, i.e., cotton – the economic capitol of Cedar Grove Plantation. Commodity crops are still a mainstay of today’s agriculture. Dr. Kasper asked the audience: of the 4.5 million arable acres of land available, how many acres produce fresh fruits and vegetables, not commodity crops? The answer is less than 1% or 0.05%! Less than 2,000 acres! How have food systems of the past affected food systems of today? She said, “We have fertile soil, but have chosen commodity crops over food. And it’s difficult for farmers to shift away from commodity crops to food crops. How could we move in a more equitable direction” for the distribution of fresh food?

Findings from Rhodes’ research are uncovering the everyday lives of 19th century slaves in west Tennessee. They dig in 2 x 2 meter zones to look for artifacts. Many of the items recovered are some form of ceramic ware. They also look for plant remains, identified by archaeobotanists (researchers who study plant remains). They have found about 24 pipes and examined the pipe residue, discovering that people smoked not just tobacco, but also menthol, jimsonweed, and hallucinogenics.

Some of the personal items they have found include beads, most of European origin, but some may have come from Africa. They have found buckles, buttons, and parts of jewelry. Among the household items found are barrel hoops, a glass stopper, an iron key, a Jews harp, lamp glass, lead balls, metal chains, a drawer pull from a piece of furniture, and two writing slates. Some of the found artifacts were on display on a table in Bryan Hall and included a horse shoe and a horse grooming item – a metal currycomb.

After the indoor presentation by Dr. Kasper, the group went to the site to see some of the excavations. The exciting find this summer is a corner where a house once stood. Two veteran Rhodes researchers, Katie Reinhart, a 2014 Rhodes graduate who is now at Univ. of Mass. Boston in the Historical Archeology MA program, and Veronica Kilanowski-Doroh, a recent Rhodes graduate, explained the process and findings of the archaeological work at Ames.

There were 248 slaves at Cedar Grove plantation and it is estimated there were at least two slave groups (may or may not have been families) residing per slave structure. Next year they plan to put in more test plots to the east of the current site, expecting to find evidence of more structures. They also know that there was a Freedman’s Bureau school at Ames, post emancipation.

Jamie Evans spoke of the important clues from the cemeteries on Ames land. He said, “Slaves lived, died, and were buried here. We know there are at least six slave cemeteries, but there are no grave stones. Yet, there are over 200 burials in just one cemetery. Slave cemeteries continued to be used in the post bellum period, too, when descendants died and were buried with their families. Even in death, slaves had no choice when or where they were buried. Night-time burials of slaves were common. Do you know why that was? The slave owners didn’t want to lose any daylight work time.” Evans wants to more definitely define the boundaries of Cedar Grove cemeteries and place some type of marker where the slaves are buried.

Moving back to Bryan Hall, it was time to hear the history of Dwight Fryer’s family. He is a descendant of enslaved persons on the Ames land, and many of his ancestors came from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, the Gullah people. He tells the “Tennissippi story,” as geographic and social boundaries overlap state political boundaries. Dwight has been “finding his roots” of his family, much as Henry Louis Gates, Jr. does the genealogical research for other families. He grew up in the Will Hunt family and his ancestors were probably owned by Fannie Dickins.

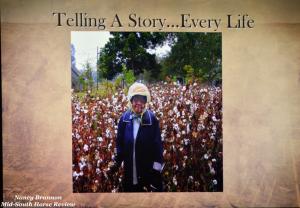

Dwight showed a photo of his mother against the background of a cotton field. Sadly, she died last year of COVID.

Fryer said there were 12½ million people kidnapped from Africa, with 400,000 brought to the U.S. The Spanish first brought slaves to this continent, and English settlers first brought slaves to Virginia in 1619.

“Cotton drove all things in Tennissippi and the Deep South,” he said, “creating the slave culture of the antebellum period, followed by the system of ‘Jim Crow’ segregation.” What are the root causes? he asked, and answered: “It’s about money, power, and sex – the land, cotton, and slaves. We pretended that slaves were not people. Some still pretend that people of color are not people.”

He introduced the group to some of the people who owned some of his ancestors, like Dr. Thomas Elijah Prewitt, John Wilkins Hunt and John Wilkins Hunt, Jr. He explained how current police behavior toward Black men is rooted in slave times: making sure the slaves were not able to escape. He explained how a free Black man had to have a white “sponsor.” He explained how today’s #MeToo movement is rooted in the exploitation of slave women. He reminded the audience that he is an American and when he uses the term “we,” he is referring to we Americans.

Fryer concluded his presentation with a moral lesson: “Life is precious. Let’s treat each of us like we’re valuable to make this world a better place.” His last slide, “We have a responsibility,” included a quote from Elie Weisel’s Night:

In the face of evil, we must summon our capacity for good. In the face of hate, we must love. In the face of cruelty, we must live with empathy and compassion. We must never be bystanders to injustice or indifferent to suffering.

Fryer is the author of two books, The Knees of Gullah Island and The Legend of Quito Road. Find more information about Dwight Fryer at: http://www.dwightfryer.com/

Find Dr. Kasper at the Rhodes College website: https://www.rhodes.edu/bio/kimberly-kasper

Find more information about the historical research at Ames at: https://www.amesplantation.org/historical-research/ Click on “Historical Document Archives” to search the document database.

Usually one sees horse people at Ames Plantation, near Grand Junction, Tenn., in December, January, and February, riding horseback in Field Trials, following champion bird dogs. But horse people and field trailers are interested in Ames history, too. And summer is the time to get updates on the archeological research at Ames.

On Saturday August 7, 2021 members of the Ames Historical Society were guests at the archaeology field day at Ames Plantation to learn the latest news from Dr. Kimberly Kasper of Rhodes College about their research at the Cedar Grove Plantation site. The group met at Bryan Hall to hear a presentation from Dr. Kasper and then to tour the recent “dig” site. This summer’s field school began on July 26 and ran for three weeks. Jamie Evans, Cultural Resources Manager at Ames, remarked, “We value our cooperative program with Rhodes College greatly. The field school allows for the recovery of a part of our history that would be impossible otherwise.”

The Ames land base is tied to prehistoric Native American towns and to people who tilled the land in later centuries. Dr. Kasper explained that while traditional “plantation archeology” focused on the owners of the plantation, that view has broadened and the Rhodes project focuses on the lives of the slaves.

Dr. Kasper’s presentation explained how archaeology is relevant in today’s world and connects the past to the present. Archaeology research can help bring more knowledge to understand how the past informs the present.

The basic theme of Rhodes’ research at Ames is Food Inequality, comparing plantation slave lifeways through archaeology with the current Memphis foodscape. The goal is to examine historical connections from the past to present food ways in order to provide solutions to the current health, socio-economic, food-based problems. Data on the current Memphis foodscape come from the Food Advisory Council, Heritage Garden, and OPCFM – the Overton Park Community Farmer’s Market.

To understand the lives of African Americans and their experiences through time and space in the south, this archaeology project utilizes historical documents and community outreach to supplement the archeology field school. Their current site of excavation is the former Cedar Grove Plantation, whose former headquarters is now the Ames Manor House.

Researchers collect oral histories from descendants of slaves still living in the area. Dwight Fryer, a descendant of slaves on the Ames land base, has provided a wealth of information to the Rhodes group, as he has done extensive research on his own family. They peruse documentary records such as slave narratives from the WPA and data from slave related archival documents and Census records on approximately 27 plantations. And the field school examines materials discovered in the “digs” at the site of former plantations on Ames property.

Their first “dig” was at Woodstock Plantation owned by Beverly Holcombe, who enslaved 42 African-Americans in the 1830s and 40s on what is today’s Ames landscape. Their second subject was the Fanny Dickins plantation, where 40 African-Americans were enslaved on property she owned from1841-1853. The current site is the larger, former Cedar Grove plantation, owned by John W. Jones from1827-1879, who owned 248 slaves, as per the 1850 slave schedule. The former slave quarters were located near where the Mule Barn sits now, and researchers expect remnants of more houses may be located to the east of their current “dig.”

Evans wrote in his quarterly newsletter that “we initially learned of the location of the quarters through an 1864 Civil War map, which indicated the cluster of houses just east of what, at that time, was the Cedar Grove manor house of John W. Jones (now the Ames Manor house). Jones was one of the most affluent planters in the region with over 4,000 acres of land, which was home to hundreds of enslaved African-Americans between 1826 and 1863.”

Evans has amassed a large collection of documentary records about the Ames Plantation, including land deeds, land entries, and slave transactions, much of which has been digitized and put on a searchable database at the website, www.amesplantation.org. Soon his team of volunteers will be adding personal letters, Bible records, court documents, newspaper articles, and more.

In her presentation, Dr. Kasper reported “what we have learned so far” from the documentary record.

· Seven of the 23 slave owners were female plantation owners

· 51% of the 674 enslaved individuals were age 15 or younger

· 40% of the enslaved individuals were between the ages of 16 and 40

· 12% of the slaves were over the age of 40

· 49% of the slaves were female and 51% were male

· 25% of the enslavers owned mulatto slaves (when mulattos were present they only comprised 10% of the population)

Dr. Kasper talked about how the slavery system was tied to commodity crops, i.e., cotton – the economic capitol of Cedar Grove Plantation. Commodity crops are still a mainstay of today’s agriculture. Dr. Kasper asked the audience: of the 4.5 million arable acres of land available, how many acres produce fresh fruits and vegetables, not commodity crops? The answer is less than 1% or 0.05%! Less than 2,000 acres! How have food systems of the past affected food systems of today? She said, “We have fertile soil, but have chosen commodity crops over food. And it’s difficult for farmers to shift away from commodity crops to food crops. How could we move in a more equitable direction” for the distribution of fresh food?

Findings from Rhodes’ research are uncovering the everyday lives of 19th century slaves in west Tennessee. They dig in 2 x 2 meter zones to look for artifacts. Many of the items recovered are some form of ceramic ware. They also look for plant remains, identified by archaeobotanists (researchers who study plant remains). They have found about 24 pipes and examined the pipe residue, discovering that people smoked not just tobacco, but also menthol, jimsonweed, and hallucinogenics.

Some of the personal items they have found include beads, most of European origin, but some may have come from Africa. They have found buckles, buttons, and parts of jewelry. Among the household items found are barrel hoops, a glass stopper, an iron key, a Jews harp, lamp glass, lead balls, metal chains, a drawer pull from a piece of furniture, and two writing slates. Some of the found artifacts were on display on a table in Bryan Hall and included a horse shoe and a horse grooming item – a metal currycomb.

After the indoor presentation by Dr. Kasper, the group went to the site to see some of the excavations. The exciting find this summer is a corner where a house once stood. Two veteran Rhodes researchers, Katie Reinhart, a 2014 Rhodes graduate who is now at Univ. of Mass. Boston in the Historical Archeology MA program, and Veronica Kilanowski-Doroh, a recent Rhodes graduate, explained the process and findings of the archaeological work at Ames.

There were 248 slaves at Cedar Grove plantation and it is estimated there were at least two slave groups (may or may not have been families) residing per slave structure. Next year they plan to put in more test plots to the east of the current site, expecting to find evidence of more structures. They also know that there was a Freedman’s Bureau school at Ames, post emancipation.

Jamie Evans spoke of the important clues from the cemeteries on Ames land. He said, “Slaves lived, died, and were buried here. We know there are at least six slave cemeteries, but there are no grave stones. Yet, there are over 200 burials in just one cemetery. Slave cemeteries continued to be used in the post bellum period, too, when descendants died and were buried with their families. Even in death, slaves had no choice when or where they were buried. Night-time burials of slaves were common. Do you know why that was? The slave owners didn’t want to lose any daylight work time.” Evans wants to more definitely define the boundaries of Cedar Grove cemeteries and place some type of marker where the slaves are buried.

Moving back to Bryan Hall, it was time to hear the history of Dwight Fryer’s family. He is a descendant of enslaved persons on the Ames land, and many of his ancestors came from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, the Gullah people. He tells the “Tennissippi story,” as geographic and social boundaries overlap state political boundaries. Dwight has been “finding his roots” of his family, much as Henry Louis Gates, Jr. does the genealogical research for other families. He grew up in the Will Hunt family and his ancestors were probably owned by Fannie Dickins.

Dwight showed a photo of his mother against the background of a cotton field. Sadly, she died last year of COVID.

Fryer said there were 12½ million people kidnapped from Africa, with 400,000 brought to the U.S. The Spanish first brought slaves to this continent, and English settlers first brought slaves to Virginia in 1619.

“Cotton drove all things in Tennissippi and the Deep South,” he said, “creating the slave culture of the antebellum period, followed by the system of ‘Jim Crow’ segregation.” What are the root causes? he asked, and answered: “It’s about money, power, and sex – the land, cotton, and slaves. We pretended that slaves were not people. Some still pretend that people of color are not people.”

He introduced the group to some of the people who owned some of his ancestors, like Dr. Thomas Elijah Prewitt, John Wilkins Hunt and John Wilkins Hunt, Jr. He explained how current police behavior toward Black men is rooted in slave times: making sure the slaves were not able to escape. He explained how a free Black man had to have a white “sponsor.” He explained how today’s #MeToo movement is rooted in the exploitation of slave women. He reminded the audience that he is an American and when he uses the term “we,” he is referring to we Americans.

Fryer concluded his presentation with a moral lesson: “Life is precious. Let’s treat each of us like we’re valuable to make this world a better place.” His last slide, “We have a responsibility,” included a quote from Elie Weisel’s Night:

In the face of evil, we must summon our capacity for good. In the face of hate, we must love. In the face of cruelty, we must live with empathy and compassion. We must never be bystanders to injustice or indifferent to suffering.

Fryer is the author of two books, The Knees of Gullah Island and The Legend of Quito Road. Find more information about Dwight Fryer at: http://www.dwightfryer.com/

Find Dr. Kasper at the Rhodes College website: https://www.rhodes.edu/bio/kimberly-kasper

Find more information about the historical research at Ames at: https://www.amesplantation.org/historical-research/ Click on “Historical Document Archives” to search the document database.