From Equine Guelph

Dr. David Mellor, a leading animal welfare expert at Massey University in New Zealand studies how bit use can impact equine breathing during exercise and what this means for equine welfare. He shared his research in a talk at the University of Guelph in autumn 2017.

One of the first topics that Mellor covered during his talk was bit-induced pain (pain that comes from bit use). Mellor introduced the topic by asking audience members to take a pen, press it lengthwise against their teeth, increase the pressure, and consider the amount of pain this caused. He then asked audience members to repeat the steps, with the pen pressed against their lower gums instead. Audience members agreed that this location produced more pain. Try this experiment for yourself. Mellor compared the sensation felt on the lower gums to the sensation felt by your horse when a bit is in their mouth. He explained that the sensation can range from mild agitation to severe pain, depending on factors like bit type and rein use.

Mellor then extended this topic to links between bit use and breathing in horses. He explained that many horses will open their mouths to deal with bit-induced pain. Unfortunately, when a horse opens his mouth, especially during intense exercise, it becomes harder for them to breathe. This is because horses breathe only with their noses, and not their mouths. In fact, a horse’s mouth actually needs to be closed for optimal breathing. When the mouth is closed, there is a negative pressure that the horse creates and maintains through swallowing. This pressure keeps the soft palate from blocking the nasopharynx. If something, like bit-induced pain, causes the mouth to open, then the pressure is disrupted and the soft palate can block the pharynx. This obstruction can cause the horse to experience breathlessness, which can impact the horse’s athletic performance. More details on the links between bit use and breathlessness in horses can be found in Mellor’s recently published literature review, “Equine Welfare during Exercise: An Evaluation of Breathing, Breathlessness and Bridles,” posted at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/7/6/41

Abstract: Horses engaged in strenuous exercise display physiological responses that approach the upper functional limits of key organ systems, in particular their cardiorespiratory systems. Maximum athletic performance is therefore vulnerable to factors that diminish these functional capacities, and such impairment might also lead to horses experiencing unpleasant respiratory sensations, i.e., breathlessness. The aim of this review is to use existing literature on equine cardiorespiratory physiology and athletic performance to evaluate the potential for various types of breathlessness to occur in exercising horses. In addition, we investigate the influence of management factors such as rein and bit use and of respiratory pathology on the likelihood and intensity of equine breathlessness occurring during exercise.

In ridden horses, rein use that reduces the jowl angle, sometimes markedly, and conditions that partially obstruct the nasopharynx and/or larynx, impair airflow in the upper respiratory tract and lead to increased flow resistance. The associated upper airway pressure changes, transmitted to the lower airways, may have pathophysiological sequelae in the alveolae, which, in their turn, may increase airflow resistance in the lower airways and impede respiratory gas exchange. Other sequelae include decreases in respiratory minute volume and worsening of the hypoxaemia, hypercapnia and acidaemia commonly observed in healthy horses during strenuous exercise.

These and other factors are implicated in the potential for ridden horses to experience three forms of breathlessness—”unpleasant respiratory effort.” “air hunger,” and “chest tightness”—which arise when there is a mismatch between a heightened ventilatory drive and the adequacy of the respiratory response. It is not known to what extent, if at all, such mismatches would occur in strenuously exercising horses unhampered by low jowl angles or by pathophysiological changes at any level of the respiratory tract. However, different combinations of the three types of breathlessness seem much more likely to occur when pathophysiological conditions significantly reduce maximal athletic performance.

Finally, most horses exhibit clear behavioral evidence of aversion to a bit in their mouths, varying from the bit being a mild irritant to very painful. This in itself is a significant animal welfare issue that should be addressed. A further major point is the potential for bits to disrupt the maintenance of negative pressure in the oropharynx, which apparently acts to prevent the soft palate from rising and obstructing the nasopharynx. The untoward respiratory outcomes and poor athletic performance due to this and other obstructions are well established, and suggest the potential for affected animals to experience significant intensities of breathlessness. Bitless bridle use may reduce or eliminate such effects. However, direct comparisons of the cardiorespiratory dynamics and the extent of any respiratory pathophysiology in horses wearing bitted and bitless bridles have not been conducted. Such studies would be helpful in confirming, or otherwise, the claimed potential benefits of bitless bridle use.

Equine Guelph’s winter 2020 online short course covers Racehorse Respiratory Health. Find more information here: https://thehorseportal.ca/course/racehorse-respiratory-health-racing/

Photo:

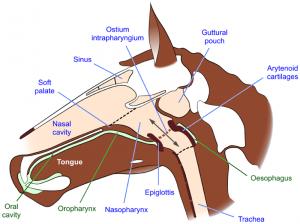

Diagram of the relationship of the soft palate and the larynx of the horse while breathing with its mouth closed. The larynx (the “button”) fits tightly into the ostium intrapharyngium (the “buttonhole”) of the soft palate, creating an airtight seal so that air cannot enter the oropharynx. This, and closed lips, would enable a negative pressure to be maintained in the oropharynx, which would hold the soft palate against the root of the tongue thereby widening the nasopharyngeal airway. Disengagement of the soft palate and larynx and/or loss of the lip seal would dissipate the negative pressure in the oropharynx, which would allow the soft palate to rise, vibrate with each breath, and impede nasopharyngeal airflow. The double-headed arrow indicates the directions of airflow.

Horses will open their mouth to escape bit pain, but this can impair their breathing, as well as their athletic performance. The open mouth also indicates resistance to bit/bridle cues, which also impedes performance.

Dr. David Mellor, a leading animal welfare expert at Massey University in New Zealand studies how bit use can impact equine breathing during exercise and what this means for equine welfare. He shared his research in a talk at the University of Guelph in autumn 2017.

One of the first topics that Mellor covered during his talk was bit-induced pain (pain that comes from bit use). Mellor introduced the topic by asking audience members to take a pen, press it lengthwise against their teeth, increase the pressure, and consider the amount of pain this caused. He then asked audience members to repeat the steps, with the pen pressed against their lower gums instead. Audience members agreed that this location produced more pain. Try this experiment for yourself. Mellor compared the sensation felt on the lower gums to the sensation felt by your horse when a bit is in their mouth. He explained that the sensation can range from mild agitation to severe pain, depending on factors like bit type and rein use.

Mellor then extended this topic to links between bit use and breathing in horses. He explained that many horses will open their mouths to deal with bit-induced pain. Unfortunately, when a horse opens his mouth, especially during intense exercise, it becomes harder for them to breathe. This is because horses breathe only with their noses, and not their mouths. In fact, a horse’s mouth actually needs to be closed for optimal breathing. When the mouth is closed, there is a negative pressure that the horse creates and maintains through swallowing. This pressure keeps the soft palate from blocking the nasopharynx. If something, like bit-induced pain, causes the mouth to open, then the pressure is disrupted and the soft palate can block the pharynx. This obstruction can cause the horse to experience breathlessness, which can impact the horse’s athletic performance. More details on the links between bit use and breathlessness in horses can be found in Mellor’s recently published literature review, “Equine Welfare during Exercise: An Evaluation of Breathing, Breathlessness and Bridles,” posted at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/7/6/41

Abstract: Horses engaged in strenuous exercise display physiological responses that approach the upper functional limits of key organ systems, in particular their cardiorespiratory systems. Maximum athletic performance is therefore vulnerable to factors that diminish these functional capacities, and such impairment might also lead to horses experiencing unpleasant respiratory sensations, i.e., breathlessness. The aim of this review is to use existing literature on equine cardiorespiratory physiology and athletic performance to evaluate the potential for various types of breathlessness to occur in exercising horses. In addition, we investigate the influence of management factors such as rein and bit use and of respiratory pathology on the likelihood and intensity of equine breathlessness occurring during exercise.

In ridden horses, rein use that reduces the jowl angle, sometimes markedly, and conditions that partially obstruct the nasopharynx and/or larynx, impair airflow in the upper respiratory tract and lead to increased flow resistance. The associated upper airway pressure changes, transmitted to the lower airways, may have pathophysiological sequelae in the alveolae, which, in their turn, may increase airflow resistance in the lower airways and impede respiratory gas exchange. Other sequelae include decreases in respiratory minute volume and worsening of the hypoxaemia, hypercapnia and acidaemia commonly observed in healthy horses during strenuous exercise.

These and other factors are implicated in the potential for ridden horses to experience three forms of breathlessness—”unpleasant respiratory effort.” “air hunger,” and “chest tightness”—which arise when there is a mismatch between a heightened ventilatory drive and the adequacy of the respiratory response. It is not known to what extent, if at all, such mismatches would occur in strenuously exercising horses unhampered by low jowl angles or by pathophysiological changes at any level of the respiratory tract. However, different combinations of the three types of breathlessness seem much more likely to occur when pathophysiological conditions significantly reduce maximal athletic performance.

Finally, most horses exhibit clear behavioral evidence of aversion to a bit in their mouths, varying from the bit being a mild irritant to very painful. This in itself is a significant animal welfare issue that should be addressed. A further major point is the potential for bits to disrupt the maintenance of negative pressure in the oropharynx, which apparently acts to prevent the soft palate from rising and obstructing the nasopharynx. The untoward respiratory outcomes and poor athletic performance due to this and other obstructions are well established, and suggest the potential for affected animals to experience significant intensities of breathlessness. Bitless bridle use may reduce or eliminate such effects. However, direct comparisons of the cardiorespiratory dynamics and the extent of any respiratory pathophysiology in horses wearing bitted and bitless bridles have not been conducted. Such studies would be helpful in confirming, or otherwise, the claimed potential benefits of bitless bridle use.

Equine Guelph’s winter 2020 online short course covers Racehorse Respiratory Health. Find more information here: https://thehorseportal.ca/course/racehorse-respiratory-health-racing/

Photo:

Diagram of the relationship of the soft palate and the larynx of the horse while breathing with its mouth closed. The larynx (the “button”) fits tightly into the ostium intrapharyngium (the “buttonhole”) of the soft palate, creating an airtight seal so that air cannot enter the oropharynx. This, and closed lips, would enable a negative pressure to be maintained in the oropharynx, which would hold the soft palate against the root of the tongue thereby widening the nasopharyngeal airway. Disengagement of the soft palate and larynx and/or loss of the lip seal would dissipate the negative pressure in the oropharynx, which would allow the soft palate to rise, vibrate with each breath, and impede nasopharyngeal airflow. The double-headed arrow indicates the directions of airflow.

Horses will open their mouth to escape bit pain, but this can impair their breathing, as well as their athletic performance. The open mouth also indicates resistance to bit/bridle cues, which also impedes performance.