Q: I just moved my horse to a new barn, and the barn manager asked me about his deworming history. When I said I dewormed regularly every 8 weeks, she replied that it may be unnecessary to deworm him that frequently, and that several owners preferred to have their horse’s manure checked before deworming. What do you know about this?

A: Great question, especially since it’s fall and “deworming time.” The approach to which your barn manager is referring is called strategic or individualized deworming, which is deworming only when necessary. First, let’s discuss the parasites themselves.

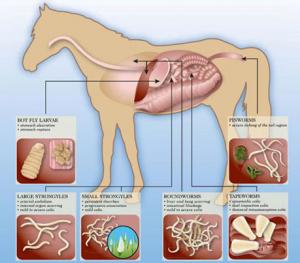

The most common parasites are the large and small strongyles. Large strongyles, referred to as “blood worms,” consist of Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus edentates and Strongylus equinus. Typical clinical signs of infestation are anemia, weakness, weight loss, and diarrhea. Anthelmentics (dewormers) used to treat large strongyles are ivermectin, moxidectin, pyrantel, and benzimidazoles.

Small strongyles, or cyathostomins, can manifest as slow growth in younger horses, poor hair coat, lethargy, weight loss, diarrhea, and colic. We see that small strongyles are now the most common parasite in our adult horse population. Dewormers used are either moxidectin or fenbendazole.

Ascarids, or roundworms, tend to be significantly more common in our younger horses, such as foals, weanling, and yearlings. Parascaris equorom causes coughing, pot belly, rough hair coat, stunted growth, and colic. Colic signs are typically seen after a foal is dewormed for the first time. Anthelmentics recommended are ivermectin and fenbendazole.

Tapeworms are caused by tiny mites that make their way into the horse’s food source. The most common are Anoplocephala magna and Paranoplocephala mamillana, which reside in the small intestine, and Anoplocephala perfoliata which is found in the ileum, ileocecal junction, and cecum. The most common clinical sign of infestation is colic, which is secondary to either intussusception (where the intestine inverts on itself, or “telescopes”) or impaction. Pyrantel and praziquantel are the anthelmintics of choice.

Other parasites found in the horse are lung worms (Dictycaulus arnfieldi), bots (Gastrophilus intestinalis, Gastrophilus nasalis, Gastrophilus haemorrhoidalis), thread worms (Strongyloides westeri), and pin worms (Oxyuris equi).

Veterinarians recommend individualized or strategic deworming instead of frequent deworming. This is done to combat anthelmintic resistance. In order to do that, we need to time our deworming with the epidemiological cycles of transmission and relative parasitic burden in individual horses.

To determine parasitic load, we recommend performing fecal egg counts, or FECs. An FEC measures how many strongyle eggs are in a gram of feces. Fecal egg counts are useful for many reasons. They allow us to determine how frequently a horse needs to be dewormed, which dewormers are effective on a farm, and what the FEC does over time. This indicates whether the parasite population is being better controlled or if possible resistance is developing. When run at your veterinarian’s office, you’ll get a number such as 20 eggs per gram (EPG) or 250 EPG. If you get 0 EPG, it does not mean your horse is parasite free, but means that either his parasite load is well controlled or that the particular parasite he does have is not shedding at the moment. This is one of the reasons why we recommend performing a FEC at least once a year.

Horses are classified as low, medium, or high shedders. A low shedder is a horse with a FEC of <200 EPG, and should be dewormed in both spring and fall. Medium shedders have between 200 and 500 EPG, and they should be dewormed in spring, late summer, and early winter. Horses with greater than 500 EPG are considered high shedders, and should be dewormed in spring, summer, fall, and winter. Your veterinarian can make the appropriate anthelmintic recommendation for each season when deworming is necessary.

Other deworming strategies recommended by the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) consist of the following:

· Pick up and dispose of manure droppings in the pasture at least twice weekly.

· Mow and harrow pastures regularly to break up manure piles and expose parasite eggs and larvae to the elements.

· Rotate pastures by allowing other livestock, such as sheep or cattle, to graze them, thereby interrupting the life cycles of parasites.

· Group horses by age to reduce exposure to certain parasites and maximize the deworming program geared to that group.

· Keep the number of horses per acre to a minimum to prevent overgrazing and reduce the fecal contamination per acre.

· Use a feeder for hay and grain rather than feeding on the ground.

· Remove bot eggs quickly and regularly from the horse’s haircoat to prevent ingestion.

· Rotate deworming agents, not just brand names, to prevent chemical resistance.

Together with your veterinarian, a specific deworming program tailored to your horse’s needs can be established!

Resource: AAEP Parasite Control Guidelines

Read more about internal parasites on the AAEP website:

www.aaep.org/info/horse-health?publication=876

A: Great question, especially since it’s fall and “deworming time.” The approach to which your barn manager is referring is called strategic or individualized deworming, which is deworming only when necessary. First, let’s discuss the parasites themselves.

The most common parasites are the large and small strongyles. Large strongyles, referred to as “blood worms,” consist of Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus edentates and Strongylus equinus. Typical clinical signs of infestation are anemia, weakness, weight loss, and diarrhea. Anthelmentics (dewormers) used to treat large strongyles are ivermectin, moxidectin, pyrantel, and benzimidazoles.

Small strongyles, or cyathostomins, can manifest as slow growth in younger horses, poor hair coat, lethargy, weight loss, diarrhea, and colic. We see that small strongyles are now the most common parasite in our adult horse population. Dewormers used are either moxidectin or fenbendazole.

Ascarids, or roundworms, tend to be significantly more common in our younger horses, such as foals, weanling, and yearlings. Parascaris equorom causes coughing, pot belly, rough hair coat, stunted growth, and colic. Colic signs are typically seen after a foal is dewormed for the first time. Anthelmentics recommended are ivermectin and fenbendazole.

Tapeworms are caused by tiny mites that make their way into the horse’s food source. The most common are Anoplocephala magna and Paranoplocephala mamillana, which reside in the small intestine, and Anoplocephala perfoliata which is found in the ileum, ileocecal junction, and cecum. The most common clinical sign of infestation is colic, which is secondary to either intussusception (where the intestine inverts on itself, or “telescopes”) or impaction. Pyrantel and praziquantel are the anthelmintics of choice.

Other parasites found in the horse are lung worms (Dictycaulus arnfieldi), bots (Gastrophilus intestinalis, Gastrophilus nasalis, Gastrophilus haemorrhoidalis), thread worms (Strongyloides westeri), and pin worms (Oxyuris equi).

Veterinarians recommend individualized or strategic deworming instead of frequent deworming. This is done to combat anthelmintic resistance. In order to do that, we need to time our deworming with the epidemiological cycles of transmission and relative parasitic burden in individual horses.

To determine parasitic load, we recommend performing fecal egg counts, or FECs. An FEC measures how many strongyle eggs are in a gram of feces. Fecal egg counts are useful for many reasons. They allow us to determine how frequently a horse needs to be dewormed, which dewormers are effective on a farm, and what the FEC does over time. This indicates whether the parasite population is being better controlled or if possible resistance is developing. When run at your veterinarian’s office, you’ll get a number such as 20 eggs per gram (EPG) or 250 EPG. If you get 0 EPG, it does not mean your horse is parasite free, but means that either his parasite load is well controlled or that the particular parasite he does have is not shedding at the moment. This is one of the reasons why we recommend performing a FEC at least once a year.

Horses are classified as low, medium, or high shedders. A low shedder is a horse with a FEC of <200 EPG, and should be dewormed in both spring and fall. Medium shedders have between 200 and 500 EPG, and they should be dewormed in spring, late summer, and early winter. Horses with greater than 500 EPG are considered high shedders, and should be dewormed in spring, summer, fall, and winter. Your veterinarian can make the appropriate anthelmintic recommendation for each season when deworming is necessary.

Other deworming strategies recommended by the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) consist of the following:

· Pick up and dispose of manure droppings in the pasture at least twice weekly.

· Mow and harrow pastures regularly to break up manure piles and expose parasite eggs and larvae to the elements.

· Rotate pastures by allowing other livestock, such as sheep or cattle, to graze them, thereby interrupting the life cycles of parasites.

· Group horses by age to reduce exposure to certain parasites and maximize the deworming program geared to that group.

· Keep the number of horses per acre to a minimum to prevent overgrazing and reduce the fecal contamination per acre.

· Use a feeder for hay and grain rather than feeding on the ground.

· Remove bot eggs quickly and regularly from the horse’s haircoat to prevent ingestion.

· Rotate deworming agents, not just brand names, to prevent chemical resistance.

Together with your veterinarian, a specific deworming program tailored to your horse’s needs can be established!

Resource: AAEP Parasite Control Guidelines

Read more about internal parasites on the AAEP website:

www.aaep.org/info/horse-health?publication=876