Gillian Higgins at Horses Inside Out presented a webinar on March 2, 2022 on Head Anatomy, as related to health, performance, bridle fit and design. The webinar covers bones, muscles, nerves, and teeth of the head and, most importantly, bridle fit and design relative to the head. Specifically covering the hyoid apparatus, temporomandibular joint, and tongue, this in-depth webinar demonstrates how understanding the anatomy of the head enables us to fit a bridle and handle the head more sensitively with the comfort and performance of the horse in mind. The webinar also provides palpation and therapy techniques you can do with your own horse. Gillian uses her signature paintings on horses, drawings, intricate anatomy models, and dissection photographs and videos to illustrate the points.

Anatomy of the head doesn’t just stop there: the webinar covers connections between the head and rest of the body, particularly some of the muscle chains. For examples, did you know that the Temporal muscles are part of the Extensor Chain of muscles? Or that the Tongue is part of the Flexor Chain of muscles?

Muscles of the head include muscles of the tongue, hyoid muscles, muscles of mastication, pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles, and muscles of facial expression. Did you know that the muscles of mastication (chewing) are the largest muscles in the head?

The hyoid apparatus is composed of five pairs of bones that attach to the tongue and suspend the pharynx and larynx between the mandible bones. Learn how to palpate it, how to test for tension, and how to perform a gentle myofascial massage on your own horse.

Gillian talks about the muscles of facial expression that are so important for our horses – allowing them to move their ears, lips and nostrils. Gillian demonstrates how you can give your horse a head massage to help relieve tension. This type of massage is especially useful after a long ride, an intense schooling session, or a visit from the dentist. A nice head massage is great for bonding with your horse, too.

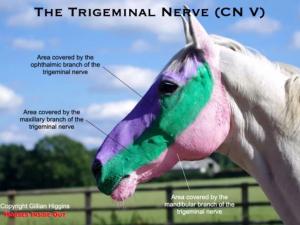

Two main nerves of the head are particularly important as related to bridle fit. These are the facial nerve and trigeminal nerves, pain from which causes symptoms such as head shaking, jaw tension, poll tension, and bit chomping. It is important to know where these nerves are located on your horse to ensure that your horse’s noseband is not putting pressure on them.

We also need to be able to locate and palpate the nasoincisive notch and ensure the noseband is not sitting lower than this, which would restrict your horse’s breathing and expansion of the nostrils.

Another consideration with nosebands is not just the position, but also the tightness. Did you know there is a high correlation between tight nosebands and dental lesions inside the cheek?

Moving to the headpiece of the bridle, Gillian explains where this should sit and why the brow band needs to be adequately sized so as not to pull the headpiece too close to the back of the ears.

The headpiece, nose band, and cheek pieces should all fit so that the buckles do not put pressure on the TMJ or Temporomandibular joint, which is a highly innervated (sensitive) joint where the lower jaw joins the skull.

Correct bridle fit is just as important at saddle fit and has a huge influence on your horse’s comfort and way of going.After watching this webinar, you can be more aware of proper bridle fit, bit action, and make your own horse more comfortable by adjusting the bridle with anatomy in mind. You can also release any tensions in their horse’s head using the therapy techniques that Gillian illustrates. Once you relieve pain in the horse’s head, your horse’s comfort and performance will be greatly improved.

You can watch the webinar here: https://www.horsesinsideout.com/webinar-head. It runs 2½ hours. In addition, Gillian’s book Illustrated Head Anatomy can be purchased on her website.

Bits and Bitting

Dwight G. Bennett, DVM, PhD gives An Overview of Bits and Bitting in a paper published by Damascus Equine.

In the section on “Proper Use of Bits and Bridles,” he writes: “Bits and bridles are for communication. They are not handles to stabilize the rider in the saddle or instruments for punishing the horse. The accomplished rider uses his seat and legs before he uses his bit to communicate his wishes to his mount. Indeed, the most important factor in achieving soft, sensitive hands on the reins is to develop a good seat.

“Bits, bridles, and accessories can exert pressure on a horse’s bars (the horseman’s term for the mandibular interdental space), lips, tongue, hard palate, chin, nose, and poll. The tongue and the hard palate are the most sensitive and the most responsive to subtle rein pressure.”

In the section on “Signs of Bitting Problems,” Bennett explains the harm that can be done to the horse’s mouth from bits. “Although laceration to the tongue is the most obvious injury associated with the improper use of bits, less spectacular injuries to the bars and other tissues are also signs of bitting problems. Tissue trapped by a bit may bunch between the bit and the first lower cheek teeth, where it is pinched or cut. The damaged area may then be irritated each time the bit moves. All types of headgear can press the lips and cheeks against points or premolar caps on the upper cheek teeth.

“A horse with a sore mouth or an improperly fitting bit will often gape its mouth and pin its ears. It may nod its head excessively or toss its head. It may extend its neck (i.e., get ahead of the bit) or tuck its chin against its chest (i.e., get behind the bit).

“The notion that a horse with a painful mouth is especially sensitive to bit cues is a common misconception. A vicious cycle can result from attempts to gain a so-called ‘hard-mouthed’ horse’s respect by changing to increasingly severe bits.”

In the next sections, Bennett describes the various types of mouthpieces and where they put pressure on the horse’s mouth. He describes the action of the broken mouthpiece versus a solid mouthpiece, which “may be straight, curved, or ported.”

He draws the distinction between what makes a mouthpiece mild and what makes it severe. Regarding bits with ports, he writes, “One of the most common misconceptions in bitting is that a low port makes a mouthpiece mild and that a high port makes it severe. As a general rule, the higher the port, the less the chance of injuring the tongue, which is the most sensitive part of the horse’s mouth. But a high port is severe when it contacts the horse’s palate. A straight, solid mouthpiece can also be severe, if used improperly, because the tongue takes almost the full force of the pull.

“A mouthpiece’s severity is inversely related to its diameter: the narrower the mouthpiece, the more severe the bit.”

From here he describes the types of “Snaffle Bits” and “Leveraged Bits.” In leverage or curb bits, “the ratio of the length of the shanks of the bit to the cheeks of the bit determines the amount ofmechanical leverage afforded to the rider. The severity of a bit increases as the ratioincreases. Yet, regardless of the ratio, the longer the shanks, the less the force on the reins is required to exert a given pressure in the mouth.” But when too much force is used on the reins, this causes pain in the horse’s mouth.

“To exert their leverage, curb bits depend on a curb chain or strap that passes beneath the horse’s chin groove and attaches to the rings on the cheeks of the bit. The bit rotates in the horse’s mouth until the curb strap stops the rotation and the leverage action of the bit takes effect. Leverage or curb bits exert pressure primarily on the chin groove, the tongue, and the bars” of the mouth.

Here it is illustrative to examine the lateral radiographs of curb bits. The first radiograph shows the bit with no rein pressure exerted. The second shows rotation of the bit under rein pressure. The third shows rein pressure on a bit with loose cheeks and a broken mouthpiece that forces the mouthpiece against the palate. The fourth shows a bit with a high port that contacts the palate, and a lateral pull of the reins with this bit force the bit against the cheek teeth.

Bennett’s next sections cover Gag Bits and Full Bridles. Again, bit action is illustrated with radiographs of bits on full bridles, with lateral views and a ventral dorsal view.

Next covered are Pelhams.

The final, most important, section is on Fitting the Bit. “The size, shape and degree of sensitivity of a horse’s mouth should be considered when selecting and fitting bits and bridles. As a rule, the mouthpiece should not project more than ½ inch or less than ¼ inch beyond the corners of the lips on either side. A mouthpiece that is too short pinches the corners of the lips against the cheek teeth. One that is too long can shift sideways, putting the port or joint out of position, making the bit ineffective and likely painful.

“The ideal position for the bit in the bar space varies from horse to horse and bit to bit. A popular rule-of-thumb for adjusting snaffles is to adjust the bit so that the commissures of the horse’s lips are pulled into one or two wrinkles. The problem with such a fit is that releasing the pressure on the reins gives the horse no relief at the corners of its mouth. A better method is to position the bit so that it is relatively loose in the mouth and then, when the horse learns to pick it up and carry it, to adjust the headstall to fix the bit at the position the horse has determined it be most comfortable.”

In conclusion, he writes that “there is no substitute for careful manual and digital examination of a horse’s mouth when selecting and properly fitting a bit. Periodic re-examination is indicated because wearing of the teeth, or even dental procedures, can change the shape of the oral cavity.”

Read the full article at:

https://damascusequine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/AnOverviewOfBitsAndBitting.pdf

Additional video resources:

Horse Bits: How They Work and When to Use, by Bernie Traurig

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y59T_CJNJ_s

Panic-Free Horsemanship has a video on Gags, Snaffles, and their Actions at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6sM3YXe5IQ This is particularly informative as bit action is illustrated using actual horse skulls.

Anatomy of the head doesn’t just stop there: the webinar covers connections between the head and rest of the body, particularly some of the muscle chains. For examples, did you know that the Temporal muscles are part of the Extensor Chain of muscles? Or that the Tongue is part of the Flexor Chain of muscles?

Muscles of the head include muscles of the tongue, hyoid muscles, muscles of mastication, pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles, and muscles of facial expression. Did you know that the muscles of mastication (chewing) are the largest muscles in the head?

The hyoid apparatus is composed of five pairs of bones that attach to the tongue and suspend the pharynx and larynx between the mandible bones. Learn how to palpate it, how to test for tension, and how to perform a gentle myofascial massage on your own horse.

Gillian talks about the muscles of facial expression that are so important for our horses – allowing them to move their ears, lips and nostrils. Gillian demonstrates how you can give your horse a head massage to help relieve tension. This type of massage is especially useful after a long ride, an intense schooling session, or a visit from the dentist. A nice head massage is great for bonding with your horse, too.

Two main nerves of the head are particularly important as related to bridle fit. These are the facial nerve and trigeminal nerves, pain from which causes symptoms such as head shaking, jaw tension, poll tension, and bit chomping. It is important to know where these nerves are located on your horse to ensure that your horse’s noseband is not putting pressure on them.

We also need to be able to locate and palpate the nasoincisive notch and ensure the noseband is not sitting lower than this, which would restrict your horse’s breathing and expansion of the nostrils.

Another consideration with nosebands is not just the position, but also the tightness. Did you know there is a high correlation between tight nosebands and dental lesions inside the cheek?

Moving to the headpiece of the bridle, Gillian explains where this should sit and why the brow band needs to be adequately sized so as not to pull the headpiece too close to the back of the ears.

The headpiece, nose band, and cheek pieces should all fit so that the buckles do not put pressure on the TMJ or Temporomandibular joint, which is a highly innervated (sensitive) joint where the lower jaw joins the skull.

Correct bridle fit is just as important at saddle fit and has a huge influence on your horse’s comfort and way of going.After watching this webinar, you can be more aware of proper bridle fit, bit action, and make your own horse more comfortable by adjusting the bridle with anatomy in mind. You can also release any tensions in their horse’s head using the therapy techniques that Gillian illustrates. Once you relieve pain in the horse’s head, your horse’s comfort and performance will be greatly improved.

You can watch the webinar here: https://www.horsesinsideout.com/webinar-head. It runs 2½ hours. In addition, Gillian’s book Illustrated Head Anatomy can be purchased on her website.

Bits and Bitting

Dwight G. Bennett, DVM, PhD gives An Overview of Bits and Bitting in a paper published by Damascus Equine.

In the section on “Proper Use of Bits and Bridles,” he writes: “Bits and bridles are for communication. They are not handles to stabilize the rider in the saddle or instruments for punishing the horse. The accomplished rider uses his seat and legs before he uses his bit to communicate his wishes to his mount. Indeed, the most important factor in achieving soft, sensitive hands on the reins is to develop a good seat.

“Bits, bridles, and accessories can exert pressure on a horse’s bars (the horseman’s term for the mandibular interdental space), lips, tongue, hard palate, chin, nose, and poll. The tongue and the hard palate are the most sensitive and the most responsive to subtle rein pressure.”

In the section on “Signs of Bitting Problems,” Bennett explains the harm that can be done to the horse’s mouth from bits. “Although laceration to the tongue is the most obvious injury associated with the improper use of bits, less spectacular injuries to the bars and other tissues are also signs of bitting problems. Tissue trapped by a bit may bunch between the bit and the first lower cheek teeth, where it is pinched or cut. The damaged area may then be irritated each time the bit moves. All types of headgear can press the lips and cheeks against points or premolar caps on the upper cheek teeth.

“A horse with a sore mouth or an improperly fitting bit will often gape its mouth and pin its ears. It may nod its head excessively or toss its head. It may extend its neck (i.e., get ahead of the bit) or tuck its chin against its chest (i.e., get behind the bit).

“The notion that a horse with a painful mouth is especially sensitive to bit cues is a common misconception. A vicious cycle can result from attempts to gain a so-called ‘hard-mouthed’ horse’s respect by changing to increasingly severe bits.”

In the next sections, Bennett describes the various types of mouthpieces and where they put pressure on the horse’s mouth. He describes the action of the broken mouthpiece versus a solid mouthpiece, which “may be straight, curved, or ported.”

He draws the distinction between what makes a mouthpiece mild and what makes it severe. Regarding bits with ports, he writes, “One of the most common misconceptions in bitting is that a low port makes a mouthpiece mild and that a high port makes it severe. As a general rule, the higher the port, the less the chance of injuring the tongue, which is the most sensitive part of the horse’s mouth. But a high port is severe when it contacts the horse’s palate. A straight, solid mouthpiece can also be severe, if used improperly, because the tongue takes almost the full force of the pull.

“A mouthpiece’s severity is inversely related to its diameter: the narrower the mouthpiece, the more severe the bit.”

From here he describes the types of “Snaffle Bits” and “Leveraged Bits.” In leverage or curb bits, “the ratio of the length of the shanks of the bit to the cheeks of the bit determines the amount ofmechanical leverage afforded to the rider. The severity of a bit increases as the ratioincreases. Yet, regardless of the ratio, the longer the shanks, the less the force on the reins is required to exert a given pressure in the mouth.” But when too much force is used on the reins, this causes pain in the horse’s mouth.

“To exert their leverage, curb bits depend on a curb chain or strap that passes beneath the horse’s chin groove and attaches to the rings on the cheeks of the bit. The bit rotates in the horse’s mouth until the curb strap stops the rotation and the leverage action of the bit takes effect. Leverage or curb bits exert pressure primarily on the chin groove, the tongue, and the bars” of the mouth.

Here it is illustrative to examine the lateral radiographs of curb bits. The first radiograph shows the bit with no rein pressure exerted. The second shows rotation of the bit under rein pressure. The third shows rein pressure on a bit with loose cheeks and a broken mouthpiece that forces the mouthpiece against the palate. The fourth shows a bit with a high port that contacts the palate, and a lateral pull of the reins with this bit force the bit against the cheek teeth.

Bennett’s next sections cover Gag Bits and Full Bridles. Again, bit action is illustrated with radiographs of bits on full bridles, with lateral views and a ventral dorsal view.

Next covered are Pelhams.

The final, most important, section is on Fitting the Bit. “The size, shape and degree of sensitivity of a horse’s mouth should be considered when selecting and fitting bits and bridles. As a rule, the mouthpiece should not project more than ½ inch or less than ¼ inch beyond the corners of the lips on either side. A mouthpiece that is too short pinches the corners of the lips against the cheek teeth. One that is too long can shift sideways, putting the port or joint out of position, making the bit ineffective and likely painful.

“The ideal position for the bit in the bar space varies from horse to horse and bit to bit. A popular rule-of-thumb for adjusting snaffles is to adjust the bit so that the commissures of the horse’s lips are pulled into one or two wrinkles. The problem with such a fit is that releasing the pressure on the reins gives the horse no relief at the corners of its mouth. A better method is to position the bit so that it is relatively loose in the mouth and then, when the horse learns to pick it up and carry it, to adjust the headstall to fix the bit at the position the horse has determined it be most comfortable.”

In conclusion, he writes that “there is no substitute for careful manual and digital examination of a horse’s mouth when selecting and properly fitting a bit. Periodic re-examination is indicated because wearing of the teeth, or even dental procedures, can change the shape of the oral cavity.”

Read the full article at:

https://damascusequine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/AnOverviewOfBitsAndBitting.pdf

Additional video resources:

Horse Bits: How They Work and When to Use, by Bernie Traurig

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y59T_CJNJ_s

Panic-Free Horsemanship has a video on Gags, Snaffles, and their Actions at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6sM3YXe5IQ This is particularly informative as bit action is illustrated using actual horse skulls.