Liberty M. Getman, DVM; Diplomate, American College of Veterinary Surgeons

The use of nuclear scintigraphy as a diagnostic tool in veterinary medicine was first described in 1977. Since that time, it has become relatively widespread, being offered at many universities and larger equine referral centers throughout the world. It has continued to provide clinically useful information in cases where routine diagnostic imaging, such as x-rays and ultrasound, have failed to reach a diagnosis. Scintigraphy is particularly useful in assessing what is happening in the musculoskeletal system real-time, as opposed to x-rays where visible changes can be the result of problems that are several weeks, months, or even years old.

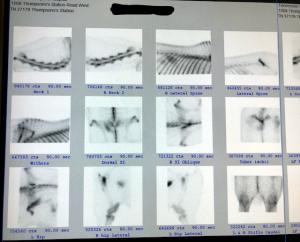

Nuclear scintigraphy, also called a “bone scan,” uses a safe radioactive drug – most commonly technetium-99m (99mTc) – administered intravenously to the horse. This drug emits radiation that is detected by a large camera positioned next to the horse, called a gamma camera. Areas of bones or joints with increases in blood flow, or with disease processes, will have greater amounts of radiation accumulate in that area. This is called increased radiopharmaceutical uptake or IRU. The IRU is captured by the gamma camera and translated using a computer program to produce a black and white image of the horse’s skeleton. Within the image, areas of normal bone will be seen, but areas with IRU will appear darker or more “hot” resulting in a “hot spot.” Hot spots indicate areas of abnormal bone or joints that can be causing lameness or pain.

Images of the horse’s skeleton are acquired at 2-4 hours after injection of technetium, with the horse awake and lightly sedated. Both normal and abnormal areas of bone emit radiation, and this radiation must travel through the soft tissues and traverse the distance from the horse’s body to the gamma camera. Therefore, areas with large muscle mass covering them (such as the pelvis or femur) or areas that cannot be positioned close to the gamma camera will have decreased radiation detected and can lead to false negative results, or to having less intense IRU than expected for a disease process. These things must be taken into account when interpreting scintigraphic images. Other factors that can lead to decreased uptake or false negatives are older horses (less metabolically active bone leading to fewer radiation binding sites), decreased blood flow, a horse that has not been in recent work, and cold ambient temperatures. Finally, if an acute injury has occurred, it is best to wait 5-7 days before performing scintigraphy to allow time for increases in blood flow and bone metabolism to occur to allow the fracture to be detected.

Nuclear scintigraphy findings must always be taken in light of the clinical findings. Many areas of the body may have mild IRU, and it is up to the referring veterinarian who performed the lameness workup, as well as the veterinarian interpreting the scintigraphy findings, to work together to determine which areas of IRU are clinically significant. It is important that a veterinarian experienced in scintigraphy interpretation read the nuclear scans, as there are many areas of “normal” IRU that could be mistaken for an abnormality if the interpreter is not experienced in reading bone scans. Conversely, there is also useful information to be obtained from a true “negative” or normal bone scan. A normal bone scan would suggest that the lameness is less likely due to a bone or joint problem and more likely due to a soft tissue or neurologic condition, and diagnostic procedures can then be targeted towards those possibilities.

Scintigraphy is particularly useful in the following situations: when trying to interpret how relevant (i.e. current) x-ray abnormalities are; to help make a diagnosis in horses with normal x-rays; for horses that do not block out using nerve or joint blocks; for horses with multiple lame limbs; for horses with performance issues that are not lame; when a stress fracture is suspected; or when pelvic, back or neck issues area suspected. Scintigraphy is significantly more sensitive than x-rays in detecting changes in bone – scintigraphy can detect changes in bone in as little as 10-13g of tissue, whereas x-rays must have changes occur in grams of bone before a problem can be seen. Therefore, scintigraphy is also useful early in the course of disease or lameness, because it will provide a diagnosis much sooner than x-rays will. This is particularly true with “bone bruising” and stress fractures. Scintigraphy can also be used to monitor horses with fractures, stress fractures or bone bruising to determine when they are ready to be put back into work.

Nuclear scintigraphy is useful in multiple clinical situations, and often investing the money and time to perform scintigraphy early-on in a complicated lameness case will lead to a quicker, more accurate diagnosis. And while scintigraphy is a slightly larger financial commitment up front, often it is less expensive than multiple lameness exams, performing excessive numbers of x-rays of multiple joints without knowing which body part is the issue, or unnecessarily medicating joints or performing other treatments without a diagnosis.

In summary, five reasons you might consider a Bone Scan:

1. My horse is not performing as well as usual.

2. I am concerned my horse may have a neck, back, pelvic, or hip issue.

3. I want to know if there are any areas that I should be concerned about prior to starting the competition season.

4. My horse is lame, and no one can figure out why.

5. My horse has lameness issues in more than one leg.

Tennessee Equine Hospital, Thompson’s Station, Tennessee, is excited to announce the arrival of a new MIE scintigraphy camera. This Gamma Camera was built in Germany and is designed to evaluate the standing horse. Its detector is one of the most sensitive on the market and combined with its motion correction software, provides beautiful images. TEH has the only scintigraphy unit in Tennessee outside of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

The use of nuclear scintigraphy as a diagnostic tool in veterinary medicine was first described in 1977. Since that time, it has become relatively widespread, being offered at many universities and larger equine referral centers throughout the world. It has continued to provide clinically useful information in cases where routine diagnostic imaging, such as x-rays and ultrasound, have failed to reach a diagnosis. Scintigraphy is particularly useful in assessing what is happening in the musculoskeletal system real-time, as opposed to x-rays where visible changes can be the result of problems that are several weeks, months, or even years old.

Nuclear scintigraphy, also called a “bone scan,” uses a safe radioactive drug – most commonly technetium-99m (99mTc) – administered intravenously to the horse. This drug emits radiation that is detected by a large camera positioned next to the horse, called a gamma camera. Areas of bones or joints with increases in blood flow, or with disease processes, will have greater amounts of radiation accumulate in that area. This is called increased radiopharmaceutical uptake or IRU. The IRU is captured by the gamma camera and translated using a computer program to produce a black and white image of the horse’s skeleton. Within the image, areas of normal bone will be seen, but areas with IRU will appear darker or more “hot” resulting in a “hot spot.” Hot spots indicate areas of abnormal bone or joints that can be causing lameness or pain.

Images of the horse’s skeleton are acquired at 2-4 hours after injection of technetium, with the horse awake and lightly sedated. Both normal and abnormal areas of bone emit radiation, and this radiation must travel through the soft tissues and traverse the distance from the horse’s body to the gamma camera. Therefore, areas with large muscle mass covering them (such as the pelvis or femur) or areas that cannot be positioned close to the gamma camera will have decreased radiation detected and can lead to false negative results, or to having less intense IRU than expected for a disease process. These things must be taken into account when interpreting scintigraphic images. Other factors that can lead to decreased uptake or false negatives are older horses (less metabolically active bone leading to fewer radiation binding sites), decreased blood flow, a horse that has not been in recent work, and cold ambient temperatures. Finally, if an acute injury has occurred, it is best to wait 5-7 days before performing scintigraphy to allow time for increases in blood flow and bone metabolism to occur to allow the fracture to be detected.

Nuclear scintigraphy findings must always be taken in light of the clinical findings. Many areas of the body may have mild IRU, and it is up to the referring veterinarian who performed the lameness workup, as well as the veterinarian interpreting the scintigraphy findings, to work together to determine which areas of IRU are clinically significant. It is important that a veterinarian experienced in scintigraphy interpretation read the nuclear scans, as there are many areas of “normal” IRU that could be mistaken for an abnormality if the interpreter is not experienced in reading bone scans. Conversely, there is also useful information to be obtained from a true “negative” or normal bone scan. A normal bone scan would suggest that the lameness is less likely due to a bone or joint problem and more likely due to a soft tissue or neurologic condition, and diagnostic procedures can then be targeted towards those possibilities.

Scintigraphy is particularly useful in the following situations: when trying to interpret how relevant (i.e. current) x-ray abnormalities are; to help make a diagnosis in horses with normal x-rays; for horses that do not block out using nerve or joint blocks; for horses with multiple lame limbs; for horses with performance issues that are not lame; when a stress fracture is suspected; or when pelvic, back or neck issues area suspected. Scintigraphy is significantly more sensitive than x-rays in detecting changes in bone – scintigraphy can detect changes in bone in as little as 10-13g of tissue, whereas x-rays must have changes occur in grams of bone before a problem can be seen. Therefore, scintigraphy is also useful early in the course of disease or lameness, because it will provide a diagnosis much sooner than x-rays will. This is particularly true with “bone bruising” and stress fractures. Scintigraphy can also be used to monitor horses with fractures, stress fractures or bone bruising to determine when they are ready to be put back into work.

Nuclear scintigraphy is useful in multiple clinical situations, and often investing the money and time to perform scintigraphy early-on in a complicated lameness case will lead to a quicker, more accurate diagnosis. And while scintigraphy is a slightly larger financial commitment up front, often it is less expensive than multiple lameness exams, performing excessive numbers of x-rays of multiple joints without knowing which body part is the issue, or unnecessarily medicating joints or performing other treatments without a diagnosis.

In summary, five reasons you might consider a Bone Scan:

1. My horse is not performing as well as usual.

2. I am concerned my horse may have a neck, back, pelvic, or hip issue.

3. I want to know if there are any areas that I should be concerned about prior to starting the competition season.

4. My horse is lame, and no one can figure out why.

5. My horse has lameness issues in more than one leg.

Tennessee Equine Hospital, Thompson’s Station, Tennessee, is excited to announce the arrival of a new MIE scintigraphy camera. This Gamma Camera was built in Germany and is designed to evaluate the standing horse. Its detector is one of the most sensitive on the market and combined with its motion correction software, provides beautiful images. TEH has the only scintigraphy unit in Tennessee outside of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.