By Nancy Brannon, Ph.D.

The 2020 Mid-South Farm to Table Conference, March 2, 2020 at Christian Brothers University in Memphis, TN, brought together farmers, local food entrepreneurs, students, educators, non-profit leaders, conservationists, and a wide variety of people interested in learning more about building a better local food system. The conference was first established in 2011 with the vision that a thriving local food system would strengthen farmer livelihoods by connecting more farmers to local consumers, improve access to fresh produce, increase healthy food consumption, and stimulate economic development and job creation in the region. The keynote speakers for this year’s conference were David R. Montgomery and Anne Biklé, the husband-wife authors of three books relevant to regenerative farming: Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations (2012); The Hidden Half of Nature: The Microbial Roots of Life and Health (2016), and Growing a Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back to Life (2018), which outlines the way current farming practices can be transformed to improve soil health and restore soil fertility.

David R. Montgomery spoke first about his research that led to publishing the “Dirt Trilogy” to tell the tangled story of humanity’s relationship with soil and the microbial world.

He said that humanity loses 0.3% of our global food production capacity each year to soil erosion and degradation (UN Glogal State of the Soil Assessment, 2015). In his research on ancient civilizations, he found that soil erosion and degradation played a role in the demise of ancient civilizations, from Neolithic Europe to Classical Greece, Rome, the Southern United States, Central America, and more.

Many researchers blame deforestation on soil loss, but Montgomery blames the plow. “The invention of the plow fundamentally altered the balance between soil production and soil erosion, dramatically increasing soil erosion – and eventually, soil loss.” In his research he found that cycles of erosion and soil formation in ancient Greece began with Bronze Age erosion after introduction of plow-based agriculture.

Looking at more modern times, he showed a historic map of soil erosion in the Piedmont region of the U.S., including Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama, where some places lost more than 10 inches, and the average loss across the region was 4-10 inches, with only a small region on the eastern side of the Piedmont in North Carolina losing less than 4 inches. Montgomery showed several sides in his presentation of soil sample differences, with the richest soil always very dark brown, almost black, with organic matter in it. Less productive soils with less or no organic matter appeared light brown.

An article in the journal Sustainability 2015, 7, 2936-2960, “North American Soil Degradation: Processes, Practices, and Mitigating Strategies” by R.L. Baumhardt, B.A. Stewart, and U.M. Sainju supports Montgomery’s findings: “The soil organic matter (SOM) content of many soils in North America is only about 50% of the level present at the time they were converted from forests or prairies to farm lands.

Montgomery asked: How fast is soil eroding from farms? Answer: 1.5 mm/year. It takes less than 20 years to erode an inch of soil. How fast does nature make soil? Answer: 0.02 mm/year. It takes more than 1,000 years to make an inch of soil. The net soil loss of ~1 mm/year implies that erosion of a typical 0.5 to 1 m thick hillside slope of soil could occur in roughly 500 to 1,000 years. This is approximately the amount of time it took ancient civilizations to collapse.

To regenerate soil, there are three principles of conservation agriculture to employ:

1. Minimal or no disturbance (no-till)

2. Permanent ground cover

3. Diverse crop rotations

These general principles translate to a variety of settings, but the specific practices need to be tailored to the specific setting. Montgomery went on to show how implementing these practices can improve both soil quality and crop yields.

The first example was Dakota Lakes Research Farm in South Dakota. Here adopting no-till, cover crops, and complex plant rotations reduced inputs of diesel fuel, fertilizer, and pesticide use by more than half. The results were compared to traditional yields.

Traditional Yield Complex Rotation Yield

Soybeans: 63 bushels/acre Soybeans: 79 bushels/acre

Corn: 217 bushels/acre Corn: 235 bushels/acre

While the yields may not seem overly significant, when you reduce the costs of production, even slight gains mean more profit for the farmer.

The next example was the No-Till Center in Kumasi, Ghana. Here the traditional methods were slash and burn, compared with no-till with cover crops. Here are the results.

Erosion

Traditional: 1787 kg/ha/yr No-till: 77 kg/ha/yr

Traditional Yield No-Till Yield

Corn: 1.5 tons/ha Corn: 4.5 tons/ha

Cowpeas: 0.8 tons/ha Cowpeas: 1.5 tons/ha

In this case, the increased yields were vastly significant.

The third case is Brandt Farm in Ohio. This farm’s yield was compared with the County Average.

County Average Brandt Farm: 44-year no-till with cover crops

Full tillage, 200 lbs. N & 2.5 quarts Roundup/acre No tillage, 24 lbs. N & 1 quart Roundup/acre

Total cost: ~ $500/acre Total cost: ~ $320/acre

Corn yield: ~ 100 bushels/acre Corn yield: ~ 180 bushels/acre

At $4/bushel = net LOSS of $100/acre At $4/bushel = net GAIN of $400/acre

Here, the use of sustainable methods makes the difference between operating at a loss and operating at a profit.

Another example he gave is of a farmer utilizing grazing animals, i.e., cows and chickens, to improve soil and grasslands.

Montgomery’s conclusions: “Ditch the plow, cover up (don’t farm naked), and grow diversity.” The benefits of healthy soil include: higher farm profits, comparable yields, less fertilizer, pesticide, and fossil fuel use, increased soil carbon and water retention, with less off-site pollution.

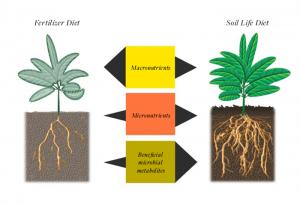

There’s another important aspect to soil degradation and that’s mineral declines in food – essential minerals that we all need for good health. Crops produced via the use of fertilizers have produced historical high yields. From 1960 to 2000, when the world’s population doubled, global grain production tripled. But there is a trade-off. High Yielding crops raised on a steady diet of fertilizers have lower levels of certain minerals and nutrients. And these deficits show up in the foods we eat. He showed significant copper decreases (76%), calcium decreases (46%), iron decreases (27%), magnesium decreases (24%), and potassium decreases (16%) in vegetable crops in a 50 year-period, ~ 1940-1990. These kinds of nutrients are the frontline prevention for many chronic diseases. Organic farming methods result in higher levels of these disease preventing nutrients in our food.

This is when Anne takes the stage and talks about her beginnings as a gardener and her “plant lust” that led to renovating their yard at their Seattle home. Thus began her “Organic Matter Chronicles.” She found that her monoculture, sterile yard needed organic matter, so she began with a Mulch Mix: decaying wood, Hinoki clippings, and assorted fresh shrub and tree leaves. She left the mulch sitting on top of the ground; it decomposed on its own; and 2-4 years later discovered they were making soil! After adding organic matter, they could see a huge difference in the quality of soil. She has a large variety of plants in her garden and has changed a “boring side yard” into a place of beauty that gives back food and improved soil.

But she didn’t make this transformation alone. She gave credit to all the forms of soil life, from beetles to worms, and more who helped break down the mulch and build soil. She explained the “hidden half of nature” and the elements that make up the “underground” network: archaea, bacteria, fungi, viruses, protists; these mesofauna are barely visible, around 1mm.

What we see above ground is only a small part of the extensive soil food web of microbes and their activities that sustain plants. “Everything going on above ground is not as important as what is going on underground.” She explained the rhizosphere, made up basically of the input of water, nutrients and minerals and root exudates. “It’s one of the most life-dense places on Earth.” [She referred to the study: “Regulation and function of root exudates,” by Dayakar V. Gadri and Jorge M. Vivanco] This “biological bazaar” [in the exudates] provides meals for microbes – carbs, fats, phytochemicals, proteins, and more. About 40% of the exudates are made from photosynthesis. The mycorrhizal fungi form a symbiotic relationship with the plant’s roots to send food to the plant and improve soil. It is a very ancient relationship – about 450 million years old. [See also Mother Earth News, “Mycorrhizal Fungi: The Amazing Underground Secret to a Better Garden” by Douglas Chadwick (2014): https://www.motherearthnews.com/organic-gardening/gardening-techniques/mycorrhizal-fungi-zm0z14aszkin]

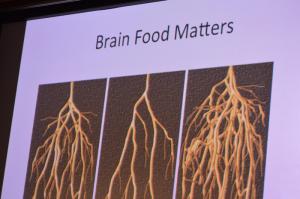

She explained the relationship between plant defense and health and how “brain food matters” in plants. In her slide on plant roots, she showed the difference in size and structure from a plant given nothing, one using conventional farming with fertilizer, and to a third nourished with composted material.

She went on to explain plant biomes and how similar they are to our own gut biomes. In the human biome, we have lots of different kinds of bacteria, mostly in our digestive tract, and most in the colon and large intestine. Our microbiome has information about our external environment and shares it with the immune system. Most of our immune system is wrapped up in the digestive tract. The immune cells are always collecting information and nutrients – “who’s a friend; who’s a foe? Who can stay and who must go?” Microbial metabolites make up our onboard medicine cabinet. And our food diet is what we feed our microbiome in the colon. So we should consume “whole plant based foods, and think of it as tranquil grazing pastures. Feed your microbiome daily!” she advised. “It’s your onboard medicine chest. You want a well-nourished microbiome.”

The “common ground” (pun intended) relationship between plant biomes and our own gut biomes is striking. These microbiomes, in both plants and humans, provide nutrients, microbial metabolites, immunity and defense, and intelligence. “We are what our microbiomes eat, too!” she concluded. In other words: “Soil Health IS Our Health.”

Biklé refers to terroir – the complete natural environment including such factors as soil, topography, climate, air, water. She also refers to E.B. (Eve) Balfour’s book, The Living Soil: Evidence of the importance to human health of soil vitality. The hypothesis is a progression from poor soil health to poor health in crops and farm animals, to sick people. “This is how infections and epidemics spread: it starts in one place with one thing and it goes on from there.”

Read more at www.dig2grow.com and in their book, The Hidden Half of Nature: the Microbial Roots of Life and Health. Also see a YouTube film of her speech to the Real Organic Project: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CWQ1i7Byi0

Find more information about this Farm to Table Conference at Memphis Tilth: https://www.memphistilth.org/farm-to-table-about

Additional Source:

Bilké, Anne and David R. Montgomery. 2016. “Junk Food Is Bad For Plants, Too.” Nautilus. March 31. http://nautil.us/issue/34/adaptation/junk-food-is-bad-for-plants-too

The 2020 Mid-South Farm to Table Conference, March 2, 2020 at Christian Brothers University in Memphis, TN, brought together farmers, local food entrepreneurs, students, educators, non-profit leaders, conservationists, and a wide variety of people interested in learning more about building a better local food system. The conference was first established in 2011 with the vision that a thriving local food system would strengthen farmer livelihoods by connecting more farmers to local consumers, improve access to fresh produce, increase healthy food consumption, and stimulate economic development and job creation in the region. The keynote speakers for this year’s conference were David R. Montgomery and Anne Biklé, the husband-wife authors of three books relevant to regenerative farming: Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations (2012); The Hidden Half of Nature: The Microbial Roots of Life and Health (2016), and Growing a Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back to Life (2018), which outlines the way current farming practices can be transformed to improve soil health and restore soil fertility.

David R. Montgomery spoke first about his research that led to publishing the “Dirt Trilogy” to tell the tangled story of humanity’s relationship with soil and the microbial world.

He said that humanity loses 0.3% of our global food production capacity each year to soil erosion and degradation (UN Glogal State of the Soil Assessment, 2015). In his research on ancient civilizations, he found that soil erosion and degradation played a role in the demise of ancient civilizations, from Neolithic Europe to Classical Greece, Rome, the Southern United States, Central America, and more.

Many researchers blame deforestation on soil loss, but Montgomery blames the plow. “The invention of the plow fundamentally altered the balance between soil production and soil erosion, dramatically increasing soil erosion – and eventually, soil loss.” In his research he found that cycles of erosion and soil formation in ancient Greece began with Bronze Age erosion after introduction of plow-based agriculture.

Looking at more modern times, he showed a historic map of soil erosion in the Piedmont region of the U.S., including Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama, where some places lost more than 10 inches, and the average loss across the region was 4-10 inches, with only a small region on the eastern side of the Piedmont in North Carolina losing less than 4 inches. Montgomery showed several sides in his presentation of soil sample differences, with the richest soil always very dark brown, almost black, with organic matter in it. Less productive soils with less or no organic matter appeared light brown.

An article in the journal Sustainability 2015, 7, 2936-2960, “North American Soil Degradation: Processes, Practices, and Mitigating Strategies” by R.L. Baumhardt, B.A. Stewart, and U.M. Sainju supports Montgomery’s findings: “The soil organic matter (SOM) content of many soils in North America is only about 50% of the level present at the time they were converted from forests or prairies to farm lands.

Montgomery asked: How fast is soil eroding from farms? Answer: 1.5 mm/year. It takes less than 20 years to erode an inch of soil. How fast does nature make soil? Answer: 0.02 mm/year. It takes more than 1,000 years to make an inch of soil. The net soil loss of ~1 mm/year implies that erosion of a typical 0.5 to 1 m thick hillside slope of soil could occur in roughly 500 to 1,000 years. This is approximately the amount of time it took ancient civilizations to collapse.

To regenerate soil, there are three principles of conservation agriculture to employ:

1. Minimal or no disturbance (no-till)

2. Permanent ground cover

3. Diverse crop rotations

These general principles translate to a variety of settings, but the specific practices need to be tailored to the specific setting. Montgomery went on to show how implementing these practices can improve both soil quality and crop yields.

The first example was Dakota Lakes Research Farm in South Dakota. Here adopting no-till, cover crops, and complex plant rotations reduced inputs of diesel fuel, fertilizer, and pesticide use by more than half. The results were compared to traditional yields.

Traditional Yield Complex Rotation Yield

Soybeans: 63 bushels/acre Soybeans: 79 bushels/acre

Corn: 217 bushels/acre Corn: 235 bushels/acre

While the yields may not seem overly significant, when you reduce the costs of production, even slight gains mean more profit for the farmer.

The next example was the No-Till Center in Kumasi, Ghana. Here the traditional methods were slash and burn, compared with no-till with cover crops. Here are the results.

Erosion

Traditional: 1787 kg/ha/yr No-till: 77 kg/ha/yr

Traditional Yield No-Till Yield

Corn: 1.5 tons/ha Corn: 4.5 tons/ha

Cowpeas: 0.8 tons/ha Cowpeas: 1.5 tons/ha

In this case, the increased yields were vastly significant.

The third case is Brandt Farm in Ohio. This farm’s yield was compared with the County Average.

County Average Brandt Farm: 44-year no-till with cover crops

Full tillage, 200 lbs. N & 2.5 quarts Roundup/acre No tillage, 24 lbs. N & 1 quart Roundup/acre

Total cost: ~ $500/acre Total cost: ~ $320/acre

Corn yield: ~ 100 bushels/acre Corn yield: ~ 180 bushels/acre

At $4/bushel = net LOSS of $100/acre At $4/bushel = net GAIN of $400/acre

Here, the use of sustainable methods makes the difference between operating at a loss and operating at a profit.

Another example he gave is of a farmer utilizing grazing animals, i.e., cows and chickens, to improve soil and grasslands.

Montgomery’s conclusions: “Ditch the plow, cover up (don’t farm naked), and grow diversity.” The benefits of healthy soil include: higher farm profits, comparable yields, less fertilizer, pesticide, and fossil fuel use, increased soil carbon and water retention, with less off-site pollution.

There’s another important aspect to soil degradation and that’s mineral declines in food – essential minerals that we all need for good health. Crops produced via the use of fertilizers have produced historical high yields. From 1960 to 2000, when the world’s population doubled, global grain production tripled. But there is a trade-off. High Yielding crops raised on a steady diet of fertilizers have lower levels of certain minerals and nutrients. And these deficits show up in the foods we eat. He showed significant copper decreases (76%), calcium decreases (46%), iron decreases (27%), magnesium decreases (24%), and potassium decreases (16%) in vegetable crops in a 50 year-period, ~ 1940-1990. These kinds of nutrients are the frontline prevention for many chronic diseases. Organic farming methods result in higher levels of these disease preventing nutrients in our food.

This is when Anne takes the stage and talks about her beginnings as a gardener and her “plant lust” that led to renovating their yard at their Seattle home. Thus began her “Organic Matter Chronicles.” She found that her monoculture, sterile yard needed organic matter, so she began with a Mulch Mix: decaying wood, Hinoki clippings, and assorted fresh shrub and tree leaves. She left the mulch sitting on top of the ground; it decomposed on its own; and 2-4 years later discovered they were making soil! After adding organic matter, they could see a huge difference in the quality of soil. She has a large variety of plants in her garden and has changed a “boring side yard” into a place of beauty that gives back food and improved soil.

But she didn’t make this transformation alone. She gave credit to all the forms of soil life, from beetles to worms, and more who helped break down the mulch and build soil. She explained the “hidden half of nature” and the elements that make up the “underground” network: archaea, bacteria, fungi, viruses, protists; these mesofauna are barely visible, around 1mm.

What we see above ground is only a small part of the extensive soil food web of microbes and their activities that sustain plants. “Everything going on above ground is not as important as what is going on underground.” She explained the rhizosphere, made up basically of the input of water, nutrients and minerals and root exudates. “It’s one of the most life-dense places on Earth.” [She referred to the study: “Regulation and function of root exudates,” by Dayakar V. Gadri and Jorge M. Vivanco] This “biological bazaar” [in the exudates] provides meals for microbes – carbs, fats, phytochemicals, proteins, and more. About 40% of the exudates are made from photosynthesis. The mycorrhizal fungi form a symbiotic relationship with the plant’s roots to send food to the plant and improve soil. It is a very ancient relationship – about 450 million years old. [See also Mother Earth News, “Mycorrhizal Fungi: The Amazing Underground Secret to a Better Garden” by Douglas Chadwick (2014): https://www.motherearthnews.com/organic-gardening/gardening-techniques/mycorrhizal-fungi-zm0z14aszkin]

She explained the relationship between plant defense and health and how “brain food matters” in plants. In her slide on plant roots, she showed the difference in size and structure from a plant given nothing, one using conventional farming with fertilizer, and to a third nourished with composted material.

She went on to explain plant biomes and how similar they are to our own gut biomes. In the human biome, we have lots of different kinds of bacteria, mostly in our digestive tract, and most in the colon and large intestine. Our microbiome has information about our external environment and shares it with the immune system. Most of our immune system is wrapped up in the digestive tract. The immune cells are always collecting information and nutrients – “who’s a friend; who’s a foe? Who can stay and who must go?” Microbial metabolites make up our onboard medicine cabinet. And our food diet is what we feed our microbiome in the colon. So we should consume “whole plant based foods, and think of it as tranquil grazing pastures. Feed your microbiome daily!” she advised. “It’s your onboard medicine chest. You want a well-nourished microbiome.”

The “common ground” (pun intended) relationship between plant biomes and our own gut biomes is striking. These microbiomes, in both plants and humans, provide nutrients, microbial metabolites, immunity and defense, and intelligence. “We are what our microbiomes eat, too!” she concluded. In other words: “Soil Health IS Our Health.”

Biklé refers to terroir – the complete natural environment including such factors as soil, topography, climate, air, water. She also refers to E.B. (Eve) Balfour’s book, The Living Soil: Evidence of the importance to human health of soil vitality. The hypothesis is a progression from poor soil health to poor health in crops and farm animals, to sick people. “This is how infections and epidemics spread: it starts in one place with one thing and it goes on from there.”

Read more at www.dig2grow.com and in their book, The Hidden Half of Nature: the Microbial Roots of Life and Health. Also see a YouTube film of her speech to the Real Organic Project: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CWQ1i7Byi0

Find more information about this Farm to Table Conference at Memphis Tilth: https://www.memphistilth.org/farm-to-table-about

Additional Source:

Bilké, Anne and David R. Montgomery. 2016. “Junk Food Is Bad For Plants, Too.” Nautilus. March 31. http://nautil.us/issue/34/adaptation/junk-food-is-bad-for-plants-too