Full Circle Equine Services of Olive Branch, Mississippi hosted an all-day Gastroscopy clinic on Wednesday March 27, 2019 from 8.a.m. - 5p.m. Dr. Hoyt Cheramie, DVM, MS, DACVS, and board certified veterinary surgeon from Boehringer Ingelheim was the guest veterinarian/ speaker. Dr. Cheramie has extensive knowledge of gastric ulcers and gastroscoping; this year he has scoped 4,000 horses so far.

The clinic had a drawing and 12 at-risk horses were chosen for a free gastroscopy. Dr. Cheramie and staff at the clinic actually ‘scoped 13 horses during the day, ranging from the 2-year-old Quarter Horse that just started training to a 19-year old-Western Pleasure horse. Twelve out of the 13 horses scoped had ulcers, and every horse that Full Circle scoped got the free evaluation.

Wednesday evening, Full Circle hosted a client educational seminar and dinner with Dr. Cheramie for the clients who participated in the gastroscoping event. It was an in-depth learning experience about gastric ulcers, focusing on prevention and treatment.

Details from Kaitlin Mielnicki, DVM:

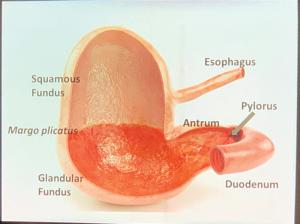

There are two portions of the stomach that can be affected by gastric ulcers - the upper, squamous portion, which is a continuation of the unprotected lining of the esophagus, and the lower, glandular portion, which secretes acid and has its own protective mechanisms from gastric acid. Ulcers can develop on either portion of the stomach lining, although most commonly occur on the squamous portion.

Typically, ulcers on the upper, squamous portion (which can be equated to heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease, “GERD,” in humans) are caused by how we manage horses - meal feedings, high concentrate diets, limited or no turnout, stress, hauling/transportation, training, showing, hospitalization, stall rest, illness, chronic pain/lameness, etc.

Research is still being done to determine the cause(s) of glandular ulcers, although we know that there is probably some loss of the innate protective mechanisms of that region, which allows ulcers to develop there.

The most common complaint of horses with ulcers is usually a change in behavior (“cinchy,” “girthy” or other irritable behavior), or they're no longer performing to the best of their abilities. Other signs of gastric ulcers in horses include picky eating or inappetence, weight loss, recurrent colic, or poor coat quality.

Another important point to note is that gastric ulcers actually cause a horse to change the way he moves, as if guarding himself from the pain/heartburn. For instance, horses that jump typically hyperextend their backs (similar to a human bending backward) as they kick their back legs up and over the jump. When they have gastric ulcers, it’s been shown that these horses jump flatter and are more likely to knock down rails. Under saddle, these horses are less supple and more short-strided in all four limbs. This can be misdiagnosed as hock or stifle issues, but the abnormal gait does not resolve with treatment of what seem to be orthopedic issues. Gastroscopy (and treatment of any gastric disease noted) may be warranted in these cases.

Consultation with a veterinarian is recommended for any horse experiencing the above signs. Gastroscopy is the only way to diagnose gastric ulcers definitively, and knowing which portion of the stomach is affected allows the veterinarian to prescribe appropriate treatment. (If no ulcers are present, then an owner can save money on the cost of a month of treatment.) Ulcers of the lower, glandular region require addition of a second medication. A re-check gastroscopy prior to termination of treatment is important, as every horse’s ulcers don't respond exactly the same. In some cases, up to 30% of the time, a horse's ulcers may require >28 days of treatment (which is standard) or the addition of other medications to help them heal. Also, it is important to note that compounded omeprazole is very unreliable and is not recommended. Only the FDA-approved product for horses should be used to prevent and to treat ulcers.

Changes in how we manage and feed our horses are vital to prevent recurrence of ulcers. Recommendations include, but are not limited to, increasing turnout time as much as possible, feeding hay in a small-hole nibble net to increase “grazing” time in the stall, decreasing the amount of concentrates (grain) in the diet when possible, adding alfalfa to the diet as a natural stomach acid buffer, ensuring horses aren't exercised on an empty stomach by allowing them to eat a bit of forage (hay or alfalfa) 30-45 minutes before work, supplementing with corn or flaxseed oil (the Omega 3 fatty acids these oils contain are anti-inflammatory), and administering ulcer prevention medication in times of stress (i.e. hauling/showing). For horse-specific or barn-specific instructions, consultation with your regular veterinarian is recommended.

The clinic had a drawing and 12 at-risk horses were chosen for a free gastroscopy. Dr. Cheramie and staff at the clinic actually ‘scoped 13 horses during the day, ranging from the 2-year-old Quarter Horse that just started training to a 19-year old-Western Pleasure horse. Twelve out of the 13 horses scoped had ulcers, and every horse that Full Circle scoped got the free evaluation.

Wednesday evening, Full Circle hosted a client educational seminar and dinner with Dr. Cheramie for the clients who participated in the gastroscoping event. It was an in-depth learning experience about gastric ulcers, focusing on prevention and treatment.

Details from Kaitlin Mielnicki, DVM:

There are two portions of the stomach that can be affected by gastric ulcers - the upper, squamous portion, which is a continuation of the unprotected lining of the esophagus, and the lower, glandular portion, which secretes acid and has its own protective mechanisms from gastric acid. Ulcers can develop on either portion of the stomach lining, although most commonly occur on the squamous portion.

Typically, ulcers on the upper, squamous portion (which can be equated to heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease, “GERD,” in humans) are caused by how we manage horses - meal feedings, high concentrate diets, limited or no turnout, stress, hauling/transportation, training, showing, hospitalization, stall rest, illness, chronic pain/lameness, etc.

Research is still being done to determine the cause(s) of glandular ulcers, although we know that there is probably some loss of the innate protective mechanisms of that region, which allows ulcers to develop there.

The most common complaint of horses with ulcers is usually a change in behavior (“cinchy,” “girthy” or other irritable behavior), or they're no longer performing to the best of their abilities. Other signs of gastric ulcers in horses include picky eating or inappetence, weight loss, recurrent colic, or poor coat quality.

Another important point to note is that gastric ulcers actually cause a horse to change the way he moves, as if guarding himself from the pain/heartburn. For instance, horses that jump typically hyperextend their backs (similar to a human bending backward) as they kick their back legs up and over the jump. When they have gastric ulcers, it’s been shown that these horses jump flatter and are more likely to knock down rails. Under saddle, these horses are less supple and more short-strided in all four limbs. This can be misdiagnosed as hock or stifle issues, but the abnormal gait does not resolve with treatment of what seem to be orthopedic issues. Gastroscopy (and treatment of any gastric disease noted) may be warranted in these cases.

Consultation with a veterinarian is recommended for any horse experiencing the above signs. Gastroscopy is the only way to diagnose gastric ulcers definitively, and knowing which portion of the stomach is affected allows the veterinarian to prescribe appropriate treatment. (If no ulcers are present, then an owner can save money on the cost of a month of treatment.) Ulcers of the lower, glandular region require addition of a second medication. A re-check gastroscopy prior to termination of treatment is important, as every horse’s ulcers don't respond exactly the same. In some cases, up to 30% of the time, a horse's ulcers may require >28 days of treatment (which is standard) or the addition of other medications to help them heal. Also, it is important to note that compounded omeprazole is very unreliable and is not recommended. Only the FDA-approved product for horses should be used to prevent and to treat ulcers.

Changes in how we manage and feed our horses are vital to prevent recurrence of ulcers. Recommendations include, but are not limited to, increasing turnout time as much as possible, feeding hay in a small-hole nibble net to increase “grazing” time in the stall, decreasing the amount of concentrates (grain) in the diet when possible, adding alfalfa to the diet as a natural stomach acid buffer, ensuring horses aren't exercised on an empty stomach by allowing them to eat a bit of forage (hay or alfalfa) 30-45 minutes before work, supplementing with corn or flaxseed oil (the Omega 3 fatty acids these oils contain are anti-inflammatory), and administering ulcer prevention medication in times of stress (i.e. hauling/showing). For horse-specific or barn-specific instructions, consultation with your regular veterinarian is recommended.