Compiled by Nancy Brannon, Ph.D.

March 22, 2019 was World Water Day, an annual UN observance day that highlights the importance of freshwater. The day is used to advocate for the sustainable management of freshwater resources all around the globe. The theme for World Water Day 2019 was “Leaving no one behind,” an adaptation of the central promise of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: as sustainable development progresses, everyone must benefit.

We all need clean drinking water to survive and thrive – including our horses, dogs, cats, and all our animals, as well as plants. This is a good time of year to explore your source of drinking water and to take action to protect it and to assure its quality and quantity for generations to come.

West Tennessee Water

West Tennessee is known for the high quality and abundance of drinking water, which comes from the underground aquifer system known as the Mississippi Embayment. The University of Memphis Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), formerly the Ground Water Institute in the Dept. of Engineering, has been studying Memphis’ groundwater for over 25 years. The following information on the source of water for west Tennessee, “Groundwater Systems of West Tennessee,” is gleaned from the University of Memphis Civil Engineering Department.

The Earth’s six billion people overtax the Earth’s supply of accessible fresh water. Both farmers and municipalities are pumping water out of the ground faster than it can be replenished. The United Nations predicts that 2.7 billion people will face severe water shortages by 2025. Currently, approximately 1.2 billion people do not have access to clean water, and more than five million people die each year from unclean water-related diseases.

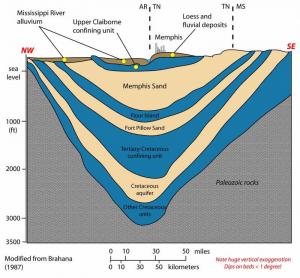

Memphis and the mid-south region are fortunate to have some of the highest quality, abundant groundwater in the world. This water comes from the multi-layered Mississippi Embayment aquifer system, a system stacked with layers of clay, sand and gravel, and sand in which the sand and/or sand and gravel layers are water-saturated. The Mississippi Embayment is a cone-shaped aquifer system that is shallower and narrower toward the north and increases in both depth and width toward the south and the Gulf of Mexico. The axis of the embayment parallels the current location of the Mississippi River.

In Shelby County, founded in 1819, there were once abundant springs that provided water for the citizenry, as well as rainwater captured in cisterns. From early on, Memphis primarily obtained its drinking water from the Wolf River. But Yellow Fever outbreaks in 1873, 1878, and 1879 nearly wiped out Memphis and forced the city to find a better, less contaminated drinking water supply than the Wolf River.

Around 1887, R.C. Graves, superintendent of the Bohlen-Huse Ice Company, dug the first artesian well in Memphis, hitting the Memphis Sand aquifer and, subsequently forming the Artesian Water Company. The City of Memphis bought the company in 1902, creating the first city-owned utility, and thus, groundwater became the primary source of the area’s drinking water.

So from there, the city of Memphis drilled wells into the aquifer at various locations around the area and developed “pumping stations” that process and distribute the municipal water system. Most of the wells are drilled into the deep, sandy layer known as the “Memphis Sands,” but some well fields have wells drilled into shallower layers of the system. Today, Memphis Light, Gas, and Water operates about 200 wells throughout Shelby County.

Memphis has a simple water processing system. First, the water pumped out of the ground is aerated to remove the iron. Next, it is run through sand and gravel filters, then a small amount of sodium hypochlorite is added to make sure the water stays uncontaminated by bacteria as it travels through the extensive pipeline distribution system.

It was long thought that any surface contaminants that could reach the deeper groundwater were prevented from reaching it by a thick clay layer called a “confining unit.” However, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) studies have found several “breaches” in the confining unit. These “breaches” or “windows” are areas where the confining clay is thin or absent. Thus, the windows provide circuit pathways for contamination to enter the aquifer.

An article by Micaela Watts in the Commercial Appeal, March 4, 2019, cited a study by the Environmental Integrity Project that revealed the presence of arsenic contamination in the shallow aquifer near the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Allen Fossil plant south of downtown Memphis. The report found it to be “one of the most polluted coal ash landfills in the country, with levels of arsenic found in the nearby groundwater at 350 times higher than what is considered safe.” The Allen Fossil plant’s three coal-powered units, that once provided electricity for Memphis, were retired in 2018.

The study, released Monday March 4, 2019, followed a recent report from the U.S. Geological Survey that revealed this contaminated groundwater is “hydraulically connected” to the Memphis Sand aquifer, the city's source for drinking water.

A report released Friday, March 1, 2019 by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) acknowledged the clay barrier separating the shallow aquifer from the deeper Memphis Sand aquifer is absent near the coal ash pond. So the threat of arsenic contamination to MLGW wells operating in the area is real, but TVA says it has been monitoring contaminates at the Allen plant, and updated their findings as recently as Friday (March 1). TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks said, “TVA is conducting a remedial investigation on the arsenic exceedances found in the shallow aquifer and has provided TDEC (Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation) with a recommended interim corrective action to address the environmental impacts.”

In the eastern stretches of the aquifer system, such as Fayette County, Tenn., the groundwater is closer to the surface and is “recharged” or replenished by infiltration of rain water – which is a good thing because this somewhat replenishes the water that is withdrawn for use. But the downside is that surface contaminants can more easily reach the groundwater and, as housing and commercial development encroach eastward, water demand increases and the potential for groundwater contamination increases. Here, man-made sources of pollution can have a direct path to the aquifer. Grading and land surface reshaping can result in a reduction of recharge to the aquifer, as rainwater increasingly runs off to streams and rivers, also increasing flooding potential. And reduced groundwater levels can affect wetland habitat. Potential sources of contamination include: landfills; contaminates in streams and rivers that have ground water connections; runoff of herbicides and pesticides from agricultural lands; septic systems; livestock waste; and outflow from wastewater treatment systems.

The Ground Water Institute was founded in 1992, housed in the University of Memphis Herff College of Engineering, to understand, improve, and protect current and future ground water quality and quantity through research, education, and application. The mission of the GWI was later expanded to CAESER, the Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research. CAESER continues ground water research in such areas as: Wellhead Protection Plans and annual Contamination Source Inventory. Water Level Survey, mapping water levels in the shallow aquifer to identify places where water of poorer quality is by passing the protective clay layer that overlies the primary drinking water aquifer. Recharge Research in Fayette County, Tennessee near the Pinecrest Center, which focuses on avenues and rates of recharge to the aquifer. Groundwater sampling at the Shelby County Landfill at Shelby Farms finds places where there are breaches in the clay confining unit that offer connectivity to the shallow aquifer. One such breach exists directly north of the former Shelby County Landfill at Shelby Farms, a landfill that was developed and closed prior to any EPA regulations that required, in the least, a liner and separation of household waste from hazardous waste. Because of leachate entering into the shallow aquifer, CAESER conducts groundwater sampling of the shallow and Memphis aquifers at this site to monitor contaminant flows.

On April 8, 2019, 6:30 – 8:00 p.m., The U of M’s Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER) will host a public meeting at the Benjamin Hooks Public Library, 3030 Poplar Avenue in Memphis, Tennessee on “Your Water, Your Research.” CAESER will host two public meetings per year on new water research projects. This is the inaugural event to hear from researchers and ask questions about your source of water. Find more about CAESER at: http://strengthencommunities.com/

The U.S. Geological Survey has an extensive collection of research date on groundwater throughout the U.S. at: https://water.usgs.gov/ogw. Here is a link to information on the Mississippi Embayment Aquifer System: https://groundwaterwatch.usgs.gov/netmapT2L1.asp?ncd=MEA. Here is a link to the Mississippi Embayment Regional Aquifer Study: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/lmg-water/science/mississippi-embayment-regional-aquifer-study-meras?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

Middle and East Tennessee Water

The source of drinking water in Knoxville, Tenn., distributed by the Knoxville Utilities Board (KUB), is the Tennessee River. KUB draws about 34 million gallons a day from the river into its water treatment plants.

KUB’s water system dates from 1883, when it was run by the Knoxville Water Company. The water plant has been in constant service since 1926, with several expansions and upgrades. On average, the plant sends 34 million gallons a day of treated water (12.4 billion gallons a year) into the distribution system, treveling through almost 1,500 miles of pipe to reach more than 77,000 customers.

Since Knoxville’s water comes from surface water, a more elaborate (and expensive) treatment system is required to ensure clean drinking to the area’s residents.

The water comes into the KUB treatment plant just downstream of where the French Broad and Holston rivers come together to form the Tennessee River. First, they treat the water with chlorine dioxide, a disinfectant that kills germs, viruses, and bacteria. Then, large screens are used to remove any debris. Next, the water is mixed with a coagulant, a chemical that helps solid particles cling together and settle out for removal. This settling process occurs in tanks called clarifiers, where most solids settle to the bottom of the tank. After the clarifiers, the water flows through large filters containing granular materials that trap remaining contaminants. KUB monitors the turbidity, or cloudiness, of the water during and after filtration. KUB uses very sensitive instruments to ensure the water meets strict turbidity requirements. The last step in the treatment process involves final disinfection with chlorine, and we add fluoride along with a zinc compound to protect pipes from corrosion. High pressure pumps then send the water into the distribution system that delivers it to homes and businesses.

Nashville gets its drinking water from the Cumberland River, with Metro Water Services the agency charged with administration of the public water system. Like Knoxville, since the public drinking water comes from surface water, a more elaborate water treatment system than Memphis’ is required, and it is similar to Knoxville’s. Metro Water Services tests for 105 substances that may be present in drinking water.

In Dec. 2018, WKRN.com Nashville reported that the growing population in the Nashville area could be putting additional strain on the drinking water infrastructure. “Our oldest water treatment plant was built in 1889, our oldest reservoir was built in 1889. Those are both still in service. Over half of our water mains are more than 40 years old. So, we have to look at the existing facilities we have and existing infrastructure and monitor it and maintain it and determine when is right for it to be repaired,” said Sonia Allman with Metro Water Services. (Read the full article here: https://www.wkrn.com/news/nashville-2018/what-impact-does-nashvilles-growing-population-have-on-drinking-water-/1655889989 )

In late summer 2017, several news sources reported on a database that was published by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group, which “compiled data from the Environmental Protection Agency and water districts to show what contaminants are contained in drinking water in utility districts across the country.” (Knox News, August 1, 2017)

“Ten harmful contaminants were found in the water supplies in 30 Tennessee towns or water utilities, according to a report released by the Environmental Working Group.” (Patch.com, July 26, 2017) Read more of this article at: https://patch.com/tennessee/nashville/30-tennessee-water-systems-have-harmful-pollutants-drinking-water-new-study-says

To access the EQG’s tap water database, go to https://www.ewg.org/tapwater/#.WXgb8NPyuqB and enter your zip code.

The groundwater in east and middle Tennessee is contained in a different type of aquifer system than in west Tennessee, called a karst system made of limestone. A report by TDEC Division of Water Resources, Drinking Water Unit, Ground Water Report 2016 (https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/environment/water/drinking-water-unit/wr_wq_report-groundwater-305b-2016.pdf ) states: “Tennessee has been blessed with an abundance of high quality and good quantity of ground water. With localized exceptions, Tennessee’s ground water is good quality as is evidenced by the number of public water systems utilizing ground water and the dozen or more bottled water facilities. Once thought to be immune from contamination, there is increasing awareness that ground water should be protected as a valuable resource.

“The vulnerability of Tennessee's ground water sources is inextricably linked to the geology of the state. Ground water can be quite vulnerable to contamination, particularly in karst terrain (limestone characterized by caves, sinkholes and springs) and in unconfined sand aquifers.”

The primary research organization studying east Tennessee water is the Tennessee Water Resources Research Center (TNWRRC), a federally designated state research institute supported in part by the U.S. Geological Survey. It is a primary link among water-resource experts in academia, government, and the private sector. TNWRRC is housed within the Institute for a Secure and Sustainable Environment (ISSE) at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tenn.

The 7th annual Watershed Symposium at UT took place March 26, 2019. This year’s theme was “Protecting and Restoring Tennessee's Waterways with Watershed Management Plans.” Keynote speaker was Dr. Sam Marshall, Director of the 319 Nonpoint Source Program for the Tennessee Department of Agriculture.

The 28th Tennessee Water Resources Symposium is held at Montgomery Bell State Park in Burns, Tenn. on April 10-12, 2019. Keynote speaker is James Dobrowolski, National Program Leader for Water and Rangeland and Grassland Ecosystems USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Find more information at: http://isse.utk.edu/wrrc/

March 22, 2019 was World Water Day, an annual UN observance day that highlights the importance of freshwater. The day is used to advocate for the sustainable management of freshwater resources all around the globe. The theme for World Water Day 2019 was “Leaving no one behind,” an adaptation of the central promise of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: as sustainable development progresses, everyone must benefit.

We all need clean drinking water to survive and thrive – including our horses, dogs, cats, and all our animals, as well as plants. This is a good time of year to explore your source of drinking water and to take action to protect it and to assure its quality and quantity for generations to come.

West Tennessee Water

West Tennessee is known for the high quality and abundance of drinking water, which comes from the underground aquifer system known as the Mississippi Embayment. The University of Memphis Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER), formerly the Ground Water Institute in the Dept. of Engineering, has been studying Memphis’ groundwater for over 25 years. The following information on the source of water for west Tennessee, “Groundwater Systems of West Tennessee,” is gleaned from the University of Memphis Civil Engineering Department.

The Earth’s six billion people overtax the Earth’s supply of accessible fresh water. Both farmers and municipalities are pumping water out of the ground faster than it can be replenished. The United Nations predicts that 2.7 billion people will face severe water shortages by 2025. Currently, approximately 1.2 billion people do not have access to clean water, and more than five million people die each year from unclean water-related diseases.

Memphis and the mid-south region are fortunate to have some of the highest quality, abundant groundwater in the world. This water comes from the multi-layered Mississippi Embayment aquifer system, a system stacked with layers of clay, sand and gravel, and sand in which the sand and/or sand and gravel layers are water-saturated. The Mississippi Embayment is a cone-shaped aquifer system that is shallower and narrower toward the north and increases in both depth and width toward the south and the Gulf of Mexico. The axis of the embayment parallels the current location of the Mississippi River.

In Shelby County, founded in 1819, there were once abundant springs that provided water for the citizenry, as well as rainwater captured in cisterns. From early on, Memphis primarily obtained its drinking water from the Wolf River. But Yellow Fever outbreaks in 1873, 1878, and 1879 nearly wiped out Memphis and forced the city to find a better, less contaminated drinking water supply than the Wolf River.

Around 1887, R.C. Graves, superintendent of the Bohlen-Huse Ice Company, dug the first artesian well in Memphis, hitting the Memphis Sand aquifer and, subsequently forming the Artesian Water Company. The City of Memphis bought the company in 1902, creating the first city-owned utility, and thus, groundwater became the primary source of the area’s drinking water.

So from there, the city of Memphis drilled wells into the aquifer at various locations around the area and developed “pumping stations” that process and distribute the municipal water system. Most of the wells are drilled into the deep, sandy layer known as the “Memphis Sands,” but some well fields have wells drilled into shallower layers of the system. Today, Memphis Light, Gas, and Water operates about 200 wells throughout Shelby County.

Memphis has a simple water processing system. First, the water pumped out of the ground is aerated to remove the iron. Next, it is run through sand and gravel filters, then a small amount of sodium hypochlorite is added to make sure the water stays uncontaminated by bacteria as it travels through the extensive pipeline distribution system.

It was long thought that any surface contaminants that could reach the deeper groundwater were prevented from reaching it by a thick clay layer called a “confining unit.” However, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) studies have found several “breaches” in the confining unit. These “breaches” or “windows” are areas where the confining clay is thin or absent. Thus, the windows provide circuit pathways for contamination to enter the aquifer.

An article by Micaela Watts in the Commercial Appeal, March 4, 2019, cited a study by the Environmental Integrity Project that revealed the presence of arsenic contamination in the shallow aquifer near the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Allen Fossil plant south of downtown Memphis. The report found it to be “one of the most polluted coal ash landfills in the country, with levels of arsenic found in the nearby groundwater at 350 times higher than what is considered safe.” The Allen Fossil plant’s three coal-powered units, that once provided electricity for Memphis, were retired in 2018.

The study, released Monday March 4, 2019, followed a recent report from the U.S. Geological Survey that revealed this contaminated groundwater is “hydraulically connected” to the Memphis Sand aquifer, the city's source for drinking water.

A report released Friday, March 1, 2019 by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) acknowledged the clay barrier separating the shallow aquifer from the deeper Memphis Sand aquifer is absent near the coal ash pond. So the threat of arsenic contamination to MLGW wells operating in the area is real, but TVA says it has been monitoring contaminates at the Allen plant, and updated their findings as recently as Friday (March 1). TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks said, “TVA is conducting a remedial investigation on the arsenic exceedances found in the shallow aquifer and has provided TDEC (Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation) with a recommended interim corrective action to address the environmental impacts.”

In the eastern stretches of the aquifer system, such as Fayette County, Tenn., the groundwater is closer to the surface and is “recharged” or replenished by infiltration of rain water – which is a good thing because this somewhat replenishes the water that is withdrawn for use. But the downside is that surface contaminants can more easily reach the groundwater and, as housing and commercial development encroach eastward, water demand increases and the potential for groundwater contamination increases. Here, man-made sources of pollution can have a direct path to the aquifer. Grading and land surface reshaping can result in a reduction of recharge to the aquifer, as rainwater increasingly runs off to streams and rivers, also increasing flooding potential. And reduced groundwater levels can affect wetland habitat. Potential sources of contamination include: landfills; contaminates in streams and rivers that have ground water connections; runoff of herbicides and pesticides from agricultural lands; septic systems; livestock waste; and outflow from wastewater treatment systems.

The Ground Water Institute was founded in 1992, housed in the University of Memphis Herff College of Engineering, to understand, improve, and protect current and future ground water quality and quantity through research, education, and application. The mission of the GWI was later expanded to CAESER, the Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research. CAESER continues ground water research in such areas as: Wellhead Protection Plans and annual Contamination Source Inventory. Water Level Survey, mapping water levels in the shallow aquifer to identify places where water of poorer quality is by passing the protective clay layer that overlies the primary drinking water aquifer. Recharge Research in Fayette County, Tennessee near the Pinecrest Center, which focuses on avenues and rates of recharge to the aquifer. Groundwater sampling at the Shelby County Landfill at Shelby Farms finds places where there are breaches in the clay confining unit that offer connectivity to the shallow aquifer. One such breach exists directly north of the former Shelby County Landfill at Shelby Farms, a landfill that was developed and closed prior to any EPA regulations that required, in the least, a liner and separation of household waste from hazardous waste. Because of leachate entering into the shallow aquifer, CAESER conducts groundwater sampling of the shallow and Memphis aquifers at this site to monitor contaminant flows.

On April 8, 2019, 6:30 – 8:00 p.m., The U of M’s Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER) will host a public meeting at the Benjamin Hooks Public Library, 3030 Poplar Avenue in Memphis, Tennessee on “Your Water, Your Research.” CAESER will host two public meetings per year on new water research projects. This is the inaugural event to hear from researchers and ask questions about your source of water. Find more about CAESER at: http://strengthencommunities.com/

The U.S. Geological Survey has an extensive collection of research date on groundwater throughout the U.S. at: https://water.usgs.gov/ogw. Here is a link to information on the Mississippi Embayment Aquifer System: https://groundwaterwatch.usgs.gov/netmapT2L1.asp?ncd=MEA. Here is a link to the Mississippi Embayment Regional Aquifer Study: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/lmg-water/science/mississippi-embayment-regional-aquifer-study-meras?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

Middle and East Tennessee Water

The source of drinking water in Knoxville, Tenn., distributed by the Knoxville Utilities Board (KUB), is the Tennessee River. KUB draws about 34 million gallons a day from the river into its water treatment plants.

KUB’s water system dates from 1883, when it was run by the Knoxville Water Company. The water plant has been in constant service since 1926, with several expansions and upgrades. On average, the plant sends 34 million gallons a day of treated water (12.4 billion gallons a year) into the distribution system, treveling through almost 1,500 miles of pipe to reach more than 77,000 customers.

Since Knoxville’s water comes from surface water, a more elaborate (and expensive) treatment system is required to ensure clean drinking to the area’s residents.

The water comes into the KUB treatment plant just downstream of where the French Broad and Holston rivers come together to form the Tennessee River. First, they treat the water with chlorine dioxide, a disinfectant that kills germs, viruses, and bacteria. Then, large screens are used to remove any debris. Next, the water is mixed with a coagulant, a chemical that helps solid particles cling together and settle out for removal. This settling process occurs in tanks called clarifiers, where most solids settle to the bottom of the tank. After the clarifiers, the water flows through large filters containing granular materials that trap remaining contaminants. KUB monitors the turbidity, or cloudiness, of the water during and after filtration. KUB uses very sensitive instruments to ensure the water meets strict turbidity requirements. The last step in the treatment process involves final disinfection with chlorine, and we add fluoride along with a zinc compound to protect pipes from corrosion. High pressure pumps then send the water into the distribution system that delivers it to homes and businesses.

Nashville gets its drinking water from the Cumberland River, with Metro Water Services the agency charged with administration of the public water system. Like Knoxville, since the public drinking water comes from surface water, a more elaborate water treatment system than Memphis’ is required, and it is similar to Knoxville’s. Metro Water Services tests for 105 substances that may be present in drinking water.

In Dec. 2018, WKRN.com Nashville reported that the growing population in the Nashville area could be putting additional strain on the drinking water infrastructure. “Our oldest water treatment plant was built in 1889, our oldest reservoir was built in 1889. Those are both still in service. Over half of our water mains are more than 40 years old. So, we have to look at the existing facilities we have and existing infrastructure and monitor it and maintain it and determine when is right for it to be repaired,” said Sonia Allman with Metro Water Services. (Read the full article here: https://www.wkrn.com/news/nashville-2018/what-impact-does-nashvilles-growing-population-have-on-drinking-water-/1655889989 )

In late summer 2017, several news sources reported on a database that was published by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group, which “compiled data from the Environmental Protection Agency and water districts to show what contaminants are contained in drinking water in utility districts across the country.” (Knox News, August 1, 2017)

“Ten harmful contaminants were found in the water supplies in 30 Tennessee towns or water utilities, according to a report released by the Environmental Working Group.” (Patch.com, July 26, 2017) Read more of this article at: https://patch.com/tennessee/nashville/30-tennessee-water-systems-have-harmful-pollutants-drinking-water-new-study-says

To access the EQG’s tap water database, go to https://www.ewg.org/tapwater/#.WXgb8NPyuqB and enter your zip code.

The groundwater in east and middle Tennessee is contained in a different type of aquifer system than in west Tennessee, called a karst system made of limestone. A report by TDEC Division of Water Resources, Drinking Water Unit, Ground Water Report 2016 (https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/environment/water/drinking-water-unit/wr_wq_report-groundwater-305b-2016.pdf ) states: “Tennessee has been blessed with an abundance of high quality and good quantity of ground water. With localized exceptions, Tennessee’s ground water is good quality as is evidenced by the number of public water systems utilizing ground water and the dozen or more bottled water facilities. Once thought to be immune from contamination, there is increasing awareness that ground water should be protected as a valuable resource.

“The vulnerability of Tennessee's ground water sources is inextricably linked to the geology of the state. Ground water can be quite vulnerable to contamination, particularly in karst terrain (limestone characterized by caves, sinkholes and springs) and in unconfined sand aquifers.”

The primary research organization studying east Tennessee water is the Tennessee Water Resources Research Center (TNWRRC), a federally designated state research institute supported in part by the U.S. Geological Survey. It is a primary link among water-resource experts in academia, government, and the private sector. TNWRRC is housed within the Institute for a Secure and Sustainable Environment (ISSE) at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tenn.

The 7th annual Watershed Symposium at UT took place March 26, 2019. This year’s theme was “Protecting and Restoring Tennessee's Waterways with Watershed Management Plans.” Keynote speaker was Dr. Sam Marshall, Director of the 319 Nonpoint Source Program for the Tennessee Department of Agriculture.

The 28th Tennessee Water Resources Symposium is held at Montgomery Bell State Park in Burns, Tenn. on April 10-12, 2019. Keynote speaker is James Dobrowolski, National Program Leader for Water and Rangeland and Grassland Ecosystems USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Find more information at: http://isse.utk.edu/wrrc/