Lexington, KY—With Keeneland’s spring meet in full swing, the 144th Kentucky Derby on May 5, the 143rd running of the Preakness on May 19, and the upcoming 150th Belmont Stakes on June 9, the nation’s attention is focused on Thoroughbred racing. The Sport of Kings has a long and storied history that is worth revisiting because of what it reveals about our broader society. Among the most famous early stars in the sport was Isaac Burns Murphy (1861–1896), one of the most dynamic jockeys of his era. Still considered one of the finest riders of all time, Murphy was the first jockey to win the Kentucky Derby three times, and his 44 percent win record remains unmatched. Despite his success, Murphy was pushed out of Thoroughbred racing when African American jockeys were forced off the track, and he died in obscurity.

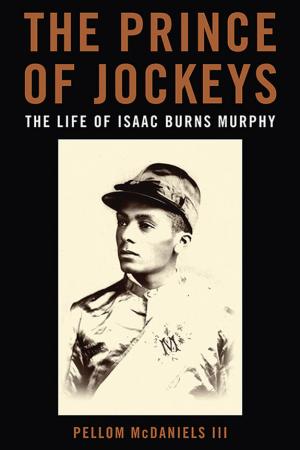

In The Prince of Jockeys: The Life of Isaac Burns Murphy, author Pellom McDaniels III offers the first definitive biography of this celebrated athlete whose life spanned the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the adoption of Jim Crow legislation. Despite the obstacles he faced, Murphy became an important figure—not just in sports, but also in the social, political, and cultural consciousness of African Americans.

Murphy’s rise as the premier jockey of his day coincided with the many opportunities that opened up for blacks in the postbellum period, especially during Reconstruction. The facts that he was able to read and write from an early age, gain access to the wealthiest Americans (who paid him well for his services), and use his purchasing power as a capitalist made him a model for resistance to popular notions of black inferiority. As African Americans like Murphy gained both socially and financially, it created a backlash among those with power, which eventually forced them out of many of the professions where they made their mark, including Thoroughbred racing.

In the spring of 1896, three months after Murphy’s death, the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson institutionalized Jim Crow segregation. His death also marked the demise of the black jockey in American horse racing. By the end of the century, only a handful of quality black jockeys could be found on American racetracks. Great riders like Anthony Hamilton (1866–1904), Willie Simms (1870–1927), and Jimmy Winkfield (1882–1974), the last black jockey to win the Kentucky Derby, were shut out by a system that favored white jockeys and wanted to rid the tracks of black competition. Eventually, all three would leave the United States to race in Europe.

Drawing from legal documents, census data, and newspapers, this comprehensive profile explores how Murphy epitomized the rise of the black middle class and contributed to the construction of popular notions about African American identity, community, and citizenship during his lifetime. The legacy of Isaac Burns Murphy is one of complex origins, a sense of purpose, and an extraordinary degree of intelligence. Lexington, Kentucky is fortunate to have him as a model of the best kind of nobility: humble, dignified, human.

About the author: Pellom McDaniels III is curator of African American Collections in the Stuart A. Rose Library at Emory University. He received a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship for The Prince of Jockeys.

In The Prince of Jockeys: The Life of Isaac Burns Murphy, author Pellom McDaniels III offers the first definitive biography of this celebrated athlete whose life spanned the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the adoption of Jim Crow legislation. Despite the obstacles he faced, Murphy became an important figure—not just in sports, but also in the social, political, and cultural consciousness of African Americans.

Murphy’s rise as the premier jockey of his day coincided with the many opportunities that opened up for blacks in the postbellum period, especially during Reconstruction. The facts that he was able to read and write from an early age, gain access to the wealthiest Americans (who paid him well for his services), and use his purchasing power as a capitalist made him a model for resistance to popular notions of black inferiority. As African Americans like Murphy gained both socially and financially, it created a backlash among those with power, which eventually forced them out of many of the professions where they made their mark, including Thoroughbred racing.

In the spring of 1896, three months after Murphy’s death, the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson institutionalized Jim Crow segregation. His death also marked the demise of the black jockey in American horse racing. By the end of the century, only a handful of quality black jockeys could be found on American racetracks. Great riders like Anthony Hamilton (1866–1904), Willie Simms (1870–1927), and Jimmy Winkfield (1882–1974), the last black jockey to win the Kentucky Derby, were shut out by a system that favored white jockeys and wanted to rid the tracks of black competition. Eventually, all three would leave the United States to race in Europe.

Drawing from legal documents, census data, and newspapers, this comprehensive profile explores how Murphy epitomized the rise of the black middle class and contributed to the construction of popular notions about African American identity, community, and citizenship during his lifetime. The legacy of Isaac Burns Murphy is one of complex origins, a sense of purpose, and an extraordinary degree of intelligence. Lexington, Kentucky is fortunate to have him as a model of the best kind of nobility: humble, dignified, human.

About the author: Pellom McDaniels III is curator of African American Collections in the Stuart A. Rose Library at Emory University. He received a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship for The Prince of Jockeys.