By Nancy Brannon, Ph.D.

In the weekly series of book signings and author interviews, Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi hosted author Walter Isaacson on May 11, 2018. Isaacson has authored in depth biographies of Steve Jobs, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Kissinger, Albert Einstein, and his latest biography is Leonardo da Vinci. In a short, 32-minute presentation, Walter Isaacson presented an engrossing portrait of Leonado da Vinci’s life and accomplishments: an artist, scientist, inventor, and supreme polymath, who was also very human and enthralled with nature and the deeply embraced the condition of life. Isaacson’s primary sources of information were the voluminous journals which Leonardo kept. Isaacson was able to locate and study approximately 700 of them.

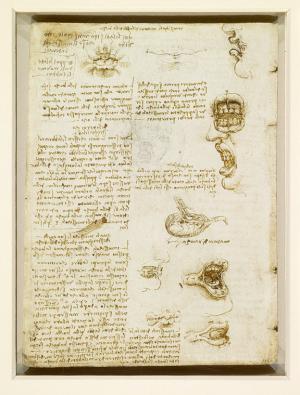

Leonardo had an extremely inquisitive mind and may well have been the greatest genius in history. Not simply the creator of some of the greatest works of art known, Leonardo’s interests combined anatomy, engineering, cartography, mathematics, architecture, botany, astronomy, geology, sculpting, and painting, which led to some creative, before-their-time inventions. Isaacson showed several images from Leonardo’s journals, many of which included “lists of things to learn today.”

Isaacson began by describing Leonardo’s early life: he was born in 1452 (d. 1519) in Vinci in the region of Florence; he was the out of wedlock son of a wealthy legal notary and a peasant woman.

At age 14, he was apprenticed to the artist Andrea del Verrocchio, the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of his day. Here Leonardo learned drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics, and carpentry, as well as the artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting, and modeling. One of his collaborative works with Verrocchio was the painting The Baptism of Christ. Isaacson showed a photo of the painting, pointing out the nuances of Leorando’s touches, especially in the faces of the two angels in the lower left. Note the curly hair and pleasant, almost smiling, look on the angel on the left (Leonardo’s), compared to the oblivious stare in the angel on the right (Verrochio’s). Isaacson also pointed out how curling lines – in the hair, in the swirling water – are important facets in many of Leonardo’s paintings and sculptures.

By the age of 20 (1472) Leonardo had qualified as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the guild of artists and doctors of medicine.

Leonardo was also a talented musician, and in 1482 created a silver lyre in the shape of a horse’s head.

Leonardo worked in Milan from 1482-1499, a time in which he painted The Last Supper for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Showing a photo of the painting, Isaacson explained how Leonardo was a story teller through his paintings.

Knowing how thoroughly Leonardo understood light and shadows, Isaacson asked the audience why – since the windows are in the back of the painting – the light falls on the right side of the painting? The answer is to view the painting in the context of the monastery in which it is displayed: here light comes into the building from windows that are on the left side of the painting.

Whatever the subject, Leonardo went to great detail to analyze and understand it, making copious notes and drawing multiple images. Isaacson pointed out that Leonardo was a perfectionist, so he periodically revised the drawings and paintings he had done.

Leonardo’s Horse is a sculpture that was commissioned by the Duke of Milan Ludovico il Moro in 1482. Leonardo did extensive preparatory work for it, but produced only a clay model, which was destroyed by French soldiers when they invaded Milan in 1499.

Isaacson detailed Leonardo’s study of anatomy, especially muscles and how they work. For example, did you know that the muscle that purses the lips is the same muscle that forms the lower lip? But a different muscle operates the upper lip. The lower lip can pucker on its own, with or without the upper lip. But it is not possible to pucker the upper lip alone (like our horses can!). It is this thorough understanding of musculature anatomy that allows Leonardo to create the most fascinating smile ever in the Mona Lisa.

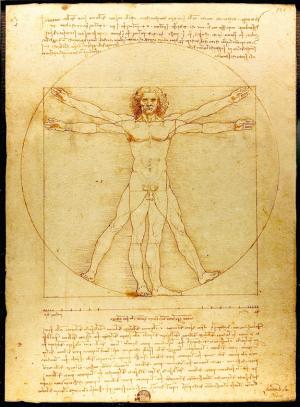

Leonardo’s ultimate understanding of balance and proportion in the human body is illustrated in his Vitruvian Man. The image is a blend of mathematics and art. Leonardo believed the workings of the human body to be an analogy for the workings of the universe, and he was always seeking to understand a unified theory of the universe. Isaacson pointed out that the man in the drawings is Leonardo himself!

The final point that Isaacson left with his audience is the importance and permanence of putting things on paper – as opposed to on a computer, on the cloud, a phone, or some other electronic device. What remnants of Leonardo’s journals are extant (Isaacson believes we may have lost perhaps 2/3 of them) are on paper and have lasted over 500 years! He compares the availability of information on Leonardo to that for his biography of Steve Jobs. Although written and stored in recent times, there was much information that Jobs was no longer able to retrieve from his computers. The lesson is that electronic postings, e.g., on a computer, on facebook or twitter, are transitory and impermanent. If you want something to last, put it on paper!

Isaacson’s fascinating presentation brought the famous genius to life and revealed some of the many aspects of Leonardo’s work and intellectual brilliance. Isaacson is Professor of History at Tulane University, and has been CEO of the Aspen Institute, chairman of CNN, and editor of Time magazine.

In the weekly series of book signings and author interviews, Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi hosted author Walter Isaacson on May 11, 2018. Isaacson has authored in depth biographies of Steve Jobs, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Kissinger, Albert Einstein, and his latest biography is Leonardo da Vinci. In a short, 32-minute presentation, Walter Isaacson presented an engrossing portrait of Leonado da Vinci’s life and accomplishments: an artist, scientist, inventor, and supreme polymath, who was also very human and enthralled with nature and the deeply embraced the condition of life. Isaacson’s primary sources of information were the voluminous journals which Leonardo kept. Isaacson was able to locate and study approximately 700 of them.

Leonardo had an extremely inquisitive mind and may well have been the greatest genius in history. Not simply the creator of some of the greatest works of art known, Leonardo’s interests combined anatomy, engineering, cartography, mathematics, architecture, botany, astronomy, geology, sculpting, and painting, which led to some creative, before-their-time inventions. Isaacson showed several images from Leonardo’s journals, many of which included “lists of things to learn today.”

Isaacson began by describing Leonardo’s early life: he was born in 1452 (d. 1519) in Vinci in the region of Florence; he was the out of wedlock son of a wealthy legal notary and a peasant woman.

At age 14, he was apprenticed to the artist Andrea del Verrocchio, the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of his day. Here Leonardo learned drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics, and carpentry, as well as the artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting, and modeling. One of his collaborative works with Verrocchio was the painting The Baptism of Christ. Isaacson showed a photo of the painting, pointing out the nuances of Leorando’s touches, especially in the faces of the two angels in the lower left. Note the curly hair and pleasant, almost smiling, look on the angel on the left (Leonardo’s), compared to the oblivious stare in the angel on the right (Verrochio’s). Isaacson also pointed out how curling lines – in the hair, in the swirling water – are important facets in many of Leonardo’s paintings and sculptures.

By the age of 20 (1472) Leonardo had qualified as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the guild of artists and doctors of medicine.

Leonardo was also a talented musician, and in 1482 created a silver lyre in the shape of a horse’s head.

Leonardo worked in Milan from 1482-1499, a time in which he painted The Last Supper for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Showing a photo of the painting, Isaacson explained how Leonardo was a story teller through his paintings.

Knowing how thoroughly Leonardo understood light and shadows, Isaacson asked the audience why – since the windows are in the back of the painting – the light falls on the right side of the painting? The answer is to view the painting in the context of the monastery in which it is displayed: here light comes into the building from windows that are on the left side of the painting.

Whatever the subject, Leonardo went to great detail to analyze and understand it, making copious notes and drawing multiple images. Isaacson pointed out that Leonardo was a perfectionist, so he periodically revised the drawings and paintings he had done.

Leonardo’s Horse is a sculpture that was commissioned by the Duke of Milan Ludovico il Moro in 1482. Leonardo did extensive preparatory work for it, but produced only a clay model, which was destroyed by French soldiers when they invaded Milan in 1499.

Isaacson detailed Leonardo’s study of anatomy, especially muscles and how they work. For example, did you know that the muscle that purses the lips is the same muscle that forms the lower lip? But a different muscle operates the upper lip. The lower lip can pucker on its own, with or without the upper lip. But it is not possible to pucker the upper lip alone (like our horses can!). It is this thorough understanding of musculature anatomy that allows Leonardo to create the most fascinating smile ever in the Mona Lisa.

Leonardo’s ultimate understanding of balance and proportion in the human body is illustrated in his Vitruvian Man. The image is a blend of mathematics and art. Leonardo believed the workings of the human body to be an analogy for the workings of the universe, and he was always seeking to understand a unified theory of the universe. Isaacson pointed out that the man in the drawings is Leonardo himself!

The final point that Isaacson left with his audience is the importance and permanence of putting things on paper – as opposed to on a computer, on the cloud, a phone, or some other electronic device. What remnants of Leonardo’s journals are extant (Isaacson believes we may have lost perhaps 2/3 of them) are on paper and have lasted over 500 years! He compares the availability of information on Leonardo to that for his biography of Steve Jobs. Although written and stored in recent times, there was much information that Jobs was no longer able to retrieve from his computers. The lesson is that electronic postings, e.g., on a computer, on facebook or twitter, are transitory and impermanent. If you want something to last, put it on paper!

Isaacson’s fascinating presentation brought the famous genius to life and revealed some of the many aspects of Leonardo’s work and intellectual brilliance. Isaacson is Professor of History at Tulane University, and has been CEO of the Aspen Institute, chairman of CNN, and editor of Time magazine.