By Leigh Ballard

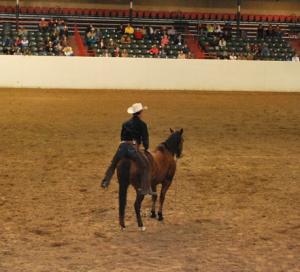

Chris Cox brought his Ride the Journey Tour to the Paul Battle Arena in Tunica, MS February 16-18. A top cowboy, horseman, and natural horsemanship clinician, Chris is known for, among other things, his unprecedented three wins at Road to the Horse. Chris works in several disciplines of western horsemanship: colt starting, roping, cutting, and cowboy dressage.

One of Chris’ main teaching points is about how human body language acts as communication to the horse. “A person’s overall expression and energy level communicate a great deal,” he says. “My expression and my body language is my first communication with my horse.” Therefore, our expressions and body language need to be energetic and “mean business” to get our expectations across to the horse.

He worked with a local horse which was 14 years old and had become habitually disrespectful and disobedient to its owner. The horse was not mean; he had simply learned that his owner would let him get away with things. Chris surmised that this problem had developed mostly because the owner/rider didn’t know how to correct the problems when they happened, or only tried halfheartedly to make corrections and then gave up. Chris said many people stop trying too soon; it is not uncommon to do so. Chris quickly engaged the horse’s mind to pay attention to him. He emphasized to the audience that time spent with our horses needs to be time well spent. “My time is limited, so what I do needs to be effective. I can’t keep doing the same thing over and over,” he said. “If it’s not working, I need to figure out why it’s not and do something different so that I make progress.” His point was that we don’t want to be reviewing and training the same thing every time we deal with a horse; the horse should be making progress.

Another of Chris’ main teaching points is how to work with a horse’s mind. Chris used the arena wall to teach the horse to move in half circles between him and the wall. “Teaching a horse to go 180 degrees is more important than going around and around in a circle, “he said. (He made it clear he was not a fan of lunging a horse mindlessly in circles.) When the horse hesitated and was confused about the exercise, Chris used the opportunity to talk about working with the horse’s mind. “It’s too much heat,” he said, as he eased up with his body language and gave the horse a little more space. “He couldn’t think. Horses get too much ‘heat’ from most people. The difference between being firm and being too hard is important. The horse has to make a decision about what you are asking. Being too hard and blocking their decision-making is not good.” Chris then used his body language to give the horse an “out” or as he called it, he was “opening the gate” for the horse by putting his body in a less pressuring position so the horse could understand where Chris wanted him to go. Eventually he moved the horse in and out of an arena gate which separated the merchandise sales area from the working arena. As the horse entered the unusual space, sniffing and with his ears up, Chris said, “He’s curious! When his mind is turning, let him stay hooked.” He progressed with controlling the horse’s movements until he was inside his merchandise area moving all around in it, and causing the horse to put his nose exactly on certain saddles, DVDs, and other merchandise!

Back in the arena, he discussed more about working with the horse’s mind. As he worked through getting the horse to accept him jumping on bareback, standing on him, sitting on his rump, and finally sliding off the back off his rump, he said, “You have to read the mind, read the indicators. I’m not worrying about him kicking me,” he said as he slid off the backside and stood behind the horse. “The kick comes from the mind, not the feet. But see, I’m patting him, stimulating him, that’s where his mind is.”

In talking about leadership Chris said, “I love for a horse to make a mistake because I have a plan.” Horses by nature seek a leader, Chris says, so the rider should always have a plan. And as a leader, the rider should never panic when things don’t go to plan. “If you are the leader and you are panicking,” he said, “Man alive, what do you think that horse is going to do?”

Chris was careful to point out that groundwork is preparation for riding. He said the “tricks” need to count for something that’s purposeful. Reading body language, expression, respect, yielding to pressure – all of these initial groundwork goals come into play when riding. He pointed out that groundwork learning also helps in other training areas, such as learning to stand tied. In response to a question from the audience he answered, “A horse should understand how to give to pressure before you ever tie him up.” And then you should tie him short and high. More horses have been seriously hurt by too long a rope.” His ropes do not have snaps. He said snaps have taught many horses to pull because the snaps break.

Chris’ Ride the Journey Tour included other aspects of horsemanship besides groundwork. Chris’s family was traveling with him and his two young children, Charley and Chase, gave a demonstration. Chris worked with a local rescue horse that had been saved from extreme neglect and near starvation.

The legendary horseman Jack Brainard was also on hand to showcase the high level of horsemanship known as Cowboy Dressage. The clinic was free, and it included Roy Cox who is a “dog-whisperer,” and Mark Beckte, a man who trains red-tailed hawks from horseback.

Chris Cox brought his Ride the Journey Tour to the Paul Battle Arena in Tunica, MS February 16-18. A top cowboy, horseman, and natural horsemanship clinician, Chris is known for, among other things, his unprecedented three wins at Road to the Horse. Chris works in several disciplines of western horsemanship: colt starting, roping, cutting, and cowboy dressage.

One of Chris’ main teaching points is about how human body language acts as communication to the horse. “A person’s overall expression and energy level communicate a great deal,” he says. “My expression and my body language is my first communication with my horse.” Therefore, our expressions and body language need to be energetic and “mean business” to get our expectations across to the horse.

He worked with a local horse which was 14 years old and had become habitually disrespectful and disobedient to its owner. The horse was not mean; he had simply learned that his owner would let him get away with things. Chris surmised that this problem had developed mostly because the owner/rider didn’t know how to correct the problems when they happened, or only tried halfheartedly to make corrections and then gave up. Chris said many people stop trying too soon; it is not uncommon to do so. Chris quickly engaged the horse’s mind to pay attention to him. He emphasized to the audience that time spent with our horses needs to be time well spent. “My time is limited, so what I do needs to be effective. I can’t keep doing the same thing over and over,” he said. “If it’s not working, I need to figure out why it’s not and do something different so that I make progress.” His point was that we don’t want to be reviewing and training the same thing every time we deal with a horse; the horse should be making progress.

Another of Chris’ main teaching points is how to work with a horse’s mind. Chris used the arena wall to teach the horse to move in half circles between him and the wall. “Teaching a horse to go 180 degrees is more important than going around and around in a circle, “he said. (He made it clear he was not a fan of lunging a horse mindlessly in circles.) When the horse hesitated and was confused about the exercise, Chris used the opportunity to talk about working with the horse’s mind. “It’s too much heat,” he said, as he eased up with his body language and gave the horse a little more space. “He couldn’t think. Horses get too much ‘heat’ from most people. The difference between being firm and being too hard is important. The horse has to make a decision about what you are asking. Being too hard and blocking their decision-making is not good.” Chris then used his body language to give the horse an “out” or as he called it, he was “opening the gate” for the horse by putting his body in a less pressuring position so the horse could understand where Chris wanted him to go. Eventually he moved the horse in and out of an arena gate which separated the merchandise sales area from the working arena. As the horse entered the unusual space, sniffing and with his ears up, Chris said, “He’s curious! When his mind is turning, let him stay hooked.” He progressed with controlling the horse’s movements until he was inside his merchandise area moving all around in it, and causing the horse to put his nose exactly on certain saddles, DVDs, and other merchandise!

Back in the arena, he discussed more about working with the horse’s mind. As he worked through getting the horse to accept him jumping on bareback, standing on him, sitting on his rump, and finally sliding off the back off his rump, he said, “You have to read the mind, read the indicators. I’m not worrying about him kicking me,” he said as he slid off the backside and stood behind the horse. “The kick comes from the mind, not the feet. But see, I’m patting him, stimulating him, that’s where his mind is.”

In talking about leadership Chris said, “I love for a horse to make a mistake because I have a plan.” Horses by nature seek a leader, Chris says, so the rider should always have a plan. And as a leader, the rider should never panic when things don’t go to plan. “If you are the leader and you are panicking,” he said, “Man alive, what do you think that horse is going to do?”

Chris was careful to point out that groundwork is preparation for riding. He said the “tricks” need to count for something that’s purposeful. Reading body language, expression, respect, yielding to pressure – all of these initial groundwork goals come into play when riding. He pointed out that groundwork learning also helps in other training areas, such as learning to stand tied. In response to a question from the audience he answered, “A horse should understand how to give to pressure before you ever tie him up.” And then you should tie him short and high. More horses have been seriously hurt by too long a rope.” His ropes do not have snaps. He said snaps have taught many horses to pull because the snaps break.

Chris’ Ride the Journey Tour included other aspects of horsemanship besides groundwork. Chris’s family was traveling with him and his two young children, Charley and Chase, gave a demonstration. Chris worked with a local rescue horse that had been saved from extreme neglect and near starvation.

The legendary horseman Jack Brainard was also on hand to showcase the high level of horsemanship known as Cowboy Dressage. The clinic was free, and it included Roy Cox who is a “dog-whisperer,” and Mark Beckte, a man who trains red-tailed hawks from horseback.