By Nancy Brannon, Ph.D.

Gastric Ulcers in Horses by UC Davis [PDF]

On August 23, 2018, Tennessee Equine Hospital Memphis, located in Eads, Tenn., offered free (regularly $275) gastroscopy exams to horses, followed by an educational seminar about equine ulcers, with dinner, at 6 p.m. The event was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, maker of Gastrogard and Ulcergard, with senior equine veterinarian Hoyt Cheramie, DVM, MS, DACVS, with Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health, the presenting speaker. His topic: “Value in Preventing, Diagnosing and Treating Equine Ulcers.” Boehringer Ingelheim conducts Gastroscopy seminars throughout the year at equine veterinary practices nationwide, providing horse owners with the diagnostic examination for their horse at no charge, with medication purchase required only for those patients identified with stomach ulcers. Medication discounts and specials are available to seminar participants.

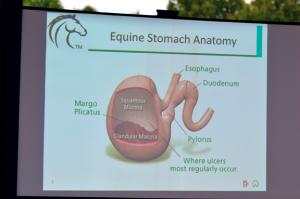

What is EQUS, Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome? There are two types (and locations): (1) Squamous disease, similar to Gastric Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in humans with “heartburn” to esophageal erosions; and (2) Glandular disease. Cheramie showed a diagram of the horse’s stomach that has squamous mucosa in the top portion and glandular mucosa in the bottom portion, a place where ulcers most regularly occur. In humans, the lining of the esophagus is squamous mucosa and all of the stomach is lined with glandular mucosa. Another difference is that horses don’t have “acid reflux” as humans do.

Humans only produce gastric acid when they eat. In contrast, horses produce gastric acid constantly, 24/7. They produce up to 16 gallons of acidic fluid every day. But grazing and chewing help buffer the acid. As horses graze, they make approximately 5,000 chews, creating about 15 gallons of saliva, with has bicarbonate in it that buffers acid. When fed grains (concentrates), horses produce even more stomach acid for digestion.

What are some risk factors that can lead to ulcers? Of important note is that all of these risk factors are created by humans.

(1) Feeding Patterns. Horses are biologically structured to graze (eat) constantly. So when under human care they are fed 1X, 2X, or 3X/day – a pattern that is contrary to their biology. Withdrawal of feed prior to work or competition is another. Cheramie says this is the wrong thing to do. Diet that favors grain and concentrates vs. hay/grass; limited or not turnout/grazing time; and changes in feeding routines, particularly when traveling, can contribute.

(2) Stress – physical stress and behavioral stress. Physical stress factors include training/competition regimens; illness and lay up time; painful disorders and lameness; and surgery. Behavioral stress includes transport/trailering; stall confinement; a new, unfamiliar environment; changes in routine; and social regrouping (new horse in the herd).

Research has shown a correlation between the levels of plasma cortisol, gastric mucosal prostaglandins, and the degree of gastric ulceration produced by stress. Continued stress raises cortisol levels. Cortisol slows the production of “good” prostaglandins. Prostaglandins (localized hormone like cellular messengers) are derived from essential fatty acids like fish oil. “Good” prostaglandins support immune function, dilate blood vessels, inhibit “thick” blood and are anti-inflammatory. Slowed production allows for the opposite - inflammation, immune suppression, etc.

Squamous Mucosa Ulcers (akaEquine Squamous Gastric Ulcer Syndrome) are caused by abnormal gastric acidity in the stomach, such as hyperacidity (too much acid) and acid where it doesn’t belong. This creates physical damage to mucosa by HCl (hydrochloric acid) and other enzymes and organic acids, all of which leads to decreased protective factors.

Glandular Ulcers (akaequine glandular gastric disease, EGGD), refers to ulceration in the ventral glandular region of the horse’s stomach , where stomach acid is produced. This condition was previously less known than Equine Squamous Gastric Ulcer Syndrome, primarily because the original endoscopes used in horses were only 2.5 meters long and were unable to reach the pyloric antum, where most glandular ulceration occurs, for visualization. With the advent of the three meter endoscope, more complete observation of the entire equine stomach is possible, and subsequent research has shown that the incidence of glandular ulceration is higher than previously believed. However, it has been less researched and less is known about their specific causes.

How ulcers occur. Whereas acidic content of the stomach “splashing” on the unprotected mucosal lining above the margo plicatus is the mechanism believed to lead to squamous ulceration in the horse, the glandular region below the margo plicatus is designed to be exposed to the highly acidic contents. The glandular mucosa is lined with gastric mucus, a complex mixture of glycoproteins, water, electrolytes, lipids, and antibodies that provide natural protection from continually secreted acids.

It is believed that the glandular ulceration, then, results from the breakdown of this protective lining, exposing the glandular mucosa to damaging acids. While there is no conclusive research indicating exactly what leads to the breakdown of this defense mechanism in the horse, NSAID use and bacterial agents have been found to be causes in humans. Cheramie said that acid injury and bacteria are unlikely primary causes in horses. It could be a defect in the protective barrier leads to erosion and gastritis/inflammation. Or is it that gastritis/inflammation leads to barrier dysfunction and erosion? Obviously, more research on this is needed.

Incidence. Cheramie’s data showed the highest incidence among racehorses – 90% (Murray et al. 1996). Mitchell (2001) found it in 63% of hunters/jumpers; in 60% of show horses generally (McClure et al. 1999), and in 40% of elite Western performance horses (Bertone 2000). It was found in 66% of all horses scoped by Merial in August 2015. [note: Merial is the developer of Gastrogard and Ulcergard (omeprazole) and was acquired by Boehringer Ingelheim in Jan. 2017.]

Clinical Signs. Some horses may not demonstrate obvious clinical signs or may have low-grade discomfort that manifests in subtle signs that may go unnoticed or be blamed on something else.

The horse may be “not quite right” at shows, be cranky, doesn’t show well or eat well. Cheramie asked, “What is the most common presenting complaint in horses diagnosed with EGUS? Poor performance!

Horses react to gastric pain in a variety of ways, Cheramie said. In 84/134 horses with ulcers studied, colic presented in 49%. The majority showed poor performance (77%), such as loss of jumping style, resistance, not yielding, stiffness, lack of response to leg aids, or “holding” their body, leading to back pain or showing as recurrent back pain. [Info from Mitchell, R. “Prevalence of Gastric Ulcers in Hunter/Jumper and Dressage Horses Evaluated for Poor Performance.”21st annual conference proceedings of the Association for Equine Sports Medicine, September 2001]

One treatment that has been used is a “stomach block,” Cheramie said, administering a combination of Maalox (aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide) along with Lidocaine through a stomach tube. Many horses will get better. But, of course, Cheramie’s recommended treatment is omeprazole in the form of GastroGard or UlcerGard.

Effects on Performance. Ulcers can have a marked effect on performance. In findings from the UC Davis study, horses without ulcers have an increase in oxygen consumption and are more efficient in using oxygen in their red blood cells to energize muscles. They have a greater increase in stride length, can run longer before tiring, and have less lactic acid build up.

Cheramie explained how this works. Horses breathe one time per stride. When the front legs reach out, they breathe in. When they do not have gastric distress, they can reach out farther, breathe longer, and therefore take in more oxygen. This increase in stride length can be 2.04 inches or greater (24.55 ft. vs. 24.38 ft.) This may not sound like much, but over the course of 1.25 miles (length of the Kentucky Derby), the increase is 45.7 ft or 5.7 lengths (268.84 strides). That’s enough to win a race!

Why do horses with ulcers have shorter strides? “Referred” gastric pain; involuntary abdominal muscle contraction.

Diagnosis. Gastroscopy is the preferred diagnostic tool. Cheramie said that of the 12 horses that were “scoped” this day at TEH, ten had grade 2 or 3 ulcers. He then showed slides of exactly what the various types, locations, and stages of ulcers look like.

Current Treatment Options.

(1) Medical Therapy – manage gastric acid. Histamine H2 receptor antagonists reduce acid production by 1/3. Acid pump inhibitors virtually stop acid production.

a. Glandular Ulcers: Proton Pump inhibitor, Sucralfate, Prostaglandin analog, Pectin-Lecithin complete, corn or flax seed oil, and if signs of infection, antibiotics. In Proton (acid) Pump inhibitors, the active ingredient is omeprazole. It inhibits the final step in acid production and suppresses acid production regardless of stimulus for up to 24 hours. It allows the pH of the stomach to increase, allowing the stomach to heal itself.

Omeprazole is a lipophilic weak base that degrades rapidly in acid aqueous solutions, in lower pH solutions (pH<7.5). It must be passed through the stomach to be absorbed in the small intestine.

From here, Cheramie showed charts that compared Gastrogard® to omeprazole from compounded pharmacies. The comparisons showed Gastrogard® had higher, more consistent, more stable levels of concentration of omeprazole than the others. He also gave examples of other non-FDA approved equine omeprazole products on the market. [For more information about one type of compounded omeprazole that was ineffective against gastric ulcers in horses, see: https://thehorse.com/130700/compounding-study-know-what-youre-getting/]

(2) Adjunctive Therapy: increased turnout with grazing or hay available. Walking has been shown to increase gastric contractility and outflow as well as colonic motility. In feeding regimens, plenty of hay (Cheramie prefers hay bags that allow the horse to get a little at a time); multiple small grain meals. Always feed hay prior to feeding grain. That stimulates saliva production, creating a physical barrier and buffering effect to stomach acid. Cheramie prefers Alfalfa Hay; it is a better buffer with with its high Calcium and Phosphorus content.

Prevention. How do we prevent ulcers? Through management – removal or reduction of ulcerogenic factors; turnout; feeding appropriate feedstuffs; continuous roughage access; alfalfa hay. Did you know that horses produce 30% more saliva when they eat off the ground?

Through pharmaceuticals, especially during high stress and ulcerogenic situations. If you use nutraceuticals or supplements, ask for the research behind them.

Cheramie recommended Ulcergard®, which has 4 doses per syringe for a 1200 pound horse. Use for 28 days. He recommended using it prior to and during stressful situations (start 48 hours out). But, Ulcergard is not cheap; the cost per tube can range from $35 per tube to $202.50 for case of 6 tubes. Ulcergard and Gastrogard are FDA approved, and currently, omeprazole is the only treatment drug approved by the FDA.

Editor’s Notes:

Unanswered questions. As with any research, the final questions asked are what factors remain unexamined/unexplained? Cheramie didn’t explain the amount of time it takes an ulcer to develop. I did not find that information in other research on equine ulcers either.

The second question is: are there other drugs that are effective in treating equine ulcers? In an article in The Horse (1999), Dr. Michael J. Murray, DVM, MS, Diplomate ACVIM, Associate Professor and Adelaide C. Riggs Chair in Equine Medicine at the Marion duPont Scott Equine Center at the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine in Leesburg, Va. gives a detailed analysis of equine gastric ulcers.

Murphy discusses two classifications of drugs used in treating equine ulcers: Acid suppressant drugs that decrease acidity in the stomach and mucosal protective drugs. There are three categories of acid suppressant drugs: (1) antacids and (2) histamine receptor type 2 (H2) antagonists, and (3) proton-pump inhibitors that block gastric acid secretion. “The only mucosal protective drug being used, says Murray, is sucralfate and it is only effective for the glandular lining of the stomach and the duodenum, where ulcers and lesions are less likely to occur.” The H2 antagonists are Murray’s drugs of choice in most cases. “Treatment with H2 antagonists,” he says, “has been successful in resolving the gastric lesions and in resolving the presenting problem. Cimetidine (Tagamet) and ranitidine (Zantac) are the most frequently used, and both inhibit gastric acid secretion in horses.”

Additional Resources:

Blue Ridge Equine, “Gastrogard Versus Ulcergard…” http://www.blueridgeequine.com/gastrogard-versus-ulcergard-protect-your-horse-from-equine-ulcers/

Kentucky Equine Research, “New Thoughts on Gastric Ulcers in Horses,” https://ker.com/equinews/new-thoughts-gastric-ulcers-horses/

Nieto, Jorge, DVM, Ph.D., DACVS, “Diagnosing and Treating Gastric Ulcers in Horses.” UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. https://www2.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/ceh/local_resources/pdfs/pubs-Oct2012-sec.pdf

Succeed Veterinary Center, “Equine Glandular Gastric Ulcer Syndrome,” https://www.succeed-vet.com/education/equine-gi-disease-library/gastritis/eggus/

The Horse, “Gastric Ulcers.” https://thehorse.com/14523/gastric-ulcers/

The Horse, “It’s Enough to Give Him an Ulcer!” https://thehorse.com/151494/its-enough-to-give-him-an-ulcer/

The Horse, “Compounding Study: Know What You’re Getting.” https://thehorse.com/130700/compounding-study-know-what-youre-getting/

Gastric Ulcers in Horses by UC Davis [PDF]

On August 23, 2018, Tennessee Equine Hospital Memphis, located in Eads, Tenn., offered free (regularly $275) gastroscopy exams to horses, followed by an educational seminar about equine ulcers, with dinner, at 6 p.m. The event was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, maker of Gastrogard and Ulcergard, with senior equine veterinarian Hoyt Cheramie, DVM, MS, DACVS, with Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health, the presenting speaker. His topic: “Value in Preventing, Diagnosing and Treating Equine Ulcers.” Boehringer Ingelheim conducts Gastroscopy seminars throughout the year at equine veterinary practices nationwide, providing horse owners with the diagnostic examination for their horse at no charge, with medication purchase required only for those patients identified with stomach ulcers. Medication discounts and specials are available to seminar participants.

What is EQUS, Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome? There are two types (and locations): (1) Squamous disease, similar to Gastric Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) in humans with “heartburn” to esophageal erosions; and (2) Glandular disease. Cheramie showed a diagram of the horse’s stomach that has squamous mucosa in the top portion and glandular mucosa in the bottom portion, a place where ulcers most regularly occur. In humans, the lining of the esophagus is squamous mucosa and all of the stomach is lined with glandular mucosa. Another difference is that horses don’t have “acid reflux” as humans do.

Humans only produce gastric acid when they eat. In contrast, horses produce gastric acid constantly, 24/7. They produce up to 16 gallons of acidic fluid every day. But grazing and chewing help buffer the acid. As horses graze, they make approximately 5,000 chews, creating about 15 gallons of saliva, with has bicarbonate in it that buffers acid. When fed grains (concentrates), horses produce even more stomach acid for digestion.

What are some risk factors that can lead to ulcers? Of important note is that all of these risk factors are created by humans.

(1) Feeding Patterns. Horses are biologically structured to graze (eat) constantly. So when under human care they are fed 1X, 2X, or 3X/day – a pattern that is contrary to their biology. Withdrawal of feed prior to work or competition is another. Cheramie says this is the wrong thing to do. Diet that favors grain and concentrates vs. hay/grass; limited or not turnout/grazing time; and changes in feeding routines, particularly when traveling, can contribute.

(2) Stress – physical stress and behavioral stress. Physical stress factors include training/competition regimens; illness and lay up time; painful disorders and lameness; and surgery. Behavioral stress includes transport/trailering; stall confinement; a new, unfamiliar environment; changes in routine; and social regrouping (new horse in the herd).

Research has shown a correlation between the levels of plasma cortisol, gastric mucosal prostaglandins, and the degree of gastric ulceration produced by stress. Continued stress raises cortisol levels. Cortisol slows the production of “good” prostaglandins. Prostaglandins (localized hormone like cellular messengers) are derived from essential fatty acids like fish oil. “Good” prostaglandins support immune function, dilate blood vessels, inhibit “thick” blood and are anti-inflammatory. Slowed production allows for the opposite - inflammation, immune suppression, etc.

Squamous Mucosa Ulcers (akaEquine Squamous Gastric Ulcer Syndrome) are caused by abnormal gastric acidity in the stomach, such as hyperacidity (too much acid) and acid where it doesn’t belong. This creates physical damage to mucosa by HCl (hydrochloric acid) and other enzymes and organic acids, all of which leads to decreased protective factors.

Glandular Ulcers (akaequine glandular gastric disease, EGGD), refers to ulceration in the ventral glandular region of the horse’s stomach , where stomach acid is produced. This condition was previously less known than Equine Squamous Gastric Ulcer Syndrome, primarily because the original endoscopes used in horses were only 2.5 meters long and were unable to reach the pyloric antum, where most glandular ulceration occurs, for visualization. With the advent of the three meter endoscope, more complete observation of the entire equine stomach is possible, and subsequent research has shown that the incidence of glandular ulceration is higher than previously believed. However, it has been less researched and less is known about their specific causes.

How ulcers occur. Whereas acidic content of the stomach “splashing” on the unprotected mucosal lining above the margo plicatus is the mechanism believed to lead to squamous ulceration in the horse, the glandular region below the margo plicatus is designed to be exposed to the highly acidic contents. The glandular mucosa is lined with gastric mucus, a complex mixture of glycoproteins, water, electrolytes, lipids, and antibodies that provide natural protection from continually secreted acids.

It is believed that the glandular ulceration, then, results from the breakdown of this protective lining, exposing the glandular mucosa to damaging acids. While there is no conclusive research indicating exactly what leads to the breakdown of this defense mechanism in the horse, NSAID use and bacterial agents have been found to be causes in humans. Cheramie said that acid injury and bacteria are unlikely primary causes in horses. It could be a defect in the protective barrier leads to erosion and gastritis/inflammation. Or is it that gastritis/inflammation leads to barrier dysfunction and erosion? Obviously, more research on this is needed.

Incidence. Cheramie’s data showed the highest incidence among racehorses – 90% (Murray et al. 1996). Mitchell (2001) found it in 63% of hunters/jumpers; in 60% of show horses generally (McClure et al. 1999), and in 40% of elite Western performance horses (Bertone 2000). It was found in 66% of all horses scoped by Merial in August 2015. [note: Merial is the developer of Gastrogard and Ulcergard (omeprazole) and was acquired by Boehringer Ingelheim in Jan. 2017.]

Clinical Signs. Some horses may not demonstrate obvious clinical signs or may have low-grade discomfort that manifests in subtle signs that may go unnoticed or be blamed on something else.

The horse may be “not quite right” at shows, be cranky, doesn’t show well or eat well. Cheramie asked, “What is the most common presenting complaint in horses diagnosed with EGUS? Poor performance!

Horses react to gastric pain in a variety of ways, Cheramie said. In 84/134 horses with ulcers studied, colic presented in 49%. The majority showed poor performance (77%), such as loss of jumping style, resistance, not yielding, stiffness, lack of response to leg aids, or “holding” their body, leading to back pain or showing as recurrent back pain. [Info from Mitchell, R. “Prevalence of Gastric Ulcers in Hunter/Jumper and Dressage Horses Evaluated for Poor Performance.”21st annual conference proceedings of the Association for Equine Sports Medicine, September 2001]

One treatment that has been used is a “stomach block,” Cheramie said, administering a combination of Maalox (aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide) along with Lidocaine through a stomach tube. Many horses will get better. But, of course, Cheramie’s recommended treatment is omeprazole in the form of GastroGard or UlcerGard.

Effects on Performance. Ulcers can have a marked effect on performance. In findings from the UC Davis study, horses without ulcers have an increase in oxygen consumption and are more efficient in using oxygen in their red blood cells to energize muscles. They have a greater increase in stride length, can run longer before tiring, and have less lactic acid build up.

Cheramie explained how this works. Horses breathe one time per stride. When the front legs reach out, they breathe in. When they do not have gastric distress, they can reach out farther, breathe longer, and therefore take in more oxygen. This increase in stride length can be 2.04 inches or greater (24.55 ft. vs. 24.38 ft.) This may not sound like much, but over the course of 1.25 miles (length of the Kentucky Derby), the increase is 45.7 ft or 5.7 lengths (268.84 strides). That’s enough to win a race!

Why do horses with ulcers have shorter strides? “Referred” gastric pain; involuntary abdominal muscle contraction.

Diagnosis. Gastroscopy is the preferred diagnostic tool. Cheramie said that of the 12 horses that were “scoped” this day at TEH, ten had grade 2 or 3 ulcers. He then showed slides of exactly what the various types, locations, and stages of ulcers look like.

Current Treatment Options.

(1) Medical Therapy – manage gastric acid. Histamine H2 receptor antagonists reduce acid production by 1/3. Acid pump inhibitors virtually stop acid production.

a. Glandular Ulcers: Proton Pump inhibitor, Sucralfate, Prostaglandin analog, Pectin-Lecithin complete, corn or flax seed oil, and if signs of infection, antibiotics. In Proton (acid) Pump inhibitors, the active ingredient is omeprazole. It inhibits the final step in acid production and suppresses acid production regardless of stimulus for up to 24 hours. It allows the pH of the stomach to increase, allowing the stomach to heal itself.

Omeprazole is a lipophilic weak base that degrades rapidly in acid aqueous solutions, in lower pH solutions (pH<7.5). It must be passed through the stomach to be absorbed in the small intestine.

From here, Cheramie showed charts that compared Gastrogard® to omeprazole from compounded pharmacies. The comparisons showed Gastrogard® had higher, more consistent, more stable levels of concentration of omeprazole than the others. He also gave examples of other non-FDA approved equine omeprazole products on the market. [For more information about one type of compounded omeprazole that was ineffective against gastric ulcers in horses, see: https://thehorse.com/130700/compounding-study-know-what-youre-getting/]

(2) Adjunctive Therapy: increased turnout with grazing or hay available. Walking has been shown to increase gastric contractility and outflow as well as colonic motility. In feeding regimens, plenty of hay (Cheramie prefers hay bags that allow the horse to get a little at a time); multiple small grain meals. Always feed hay prior to feeding grain. That stimulates saliva production, creating a physical barrier and buffering effect to stomach acid. Cheramie prefers Alfalfa Hay; it is a better buffer with with its high Calcium and Phosphorus content.

Prevention. How do we prevent ulcers? Through management – removal or reduction of ulcerogenic factors; turnout; feeding appropriate feedstuffs; continuous roughage access; alfalfa hay. Did you know that horses produce 30% more saliva when they eat off the ground?

Through pharmaceuticals, especially during high stress and ulcerogenic situations. If you use nutraceuticals or supplements, ask for the research behind them.

Cheramie recommended Ulcergard®, which has 4 doses per syringe for a 1200 pound horse. Use for 28 days. He recommended using it prior to and during stressful situations (start 48 hours out). But, Ulcergard is not cheap; the cost per tube can range from $35 per tube to $202.50 for case of 6 tubes. Ulcergard and Gastrogard are FDA approved, and currently, omeprazole is the only treatment drug approved by the FDA.

Editor’s Notes:

Unanswered questions. As with any research, the final questions asked are what factors remain unexamined/unexplained? Cheramie didn’t explain the amount of time it takes an ulcer to develop. I did not find that information in other research on equine ulcers either.

The second question is: are there other drugs that are effective in treating equine ulcers? In an article in The Horse (1999), Dr. Michael J. Murray, DVM, MS, Diplomate ACVIM, Associate Professor and Adelaide C. Riggs Chair in Equine Medicine at the Marion duPont Scott Equine Center at the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine in Leesburg, Va. gives a detailed analysis of equine gastric ulcers.

Murphy discusses two classifications of drugs used in treating equine ulcers: Acid suppressant drugs that decrease acidity in the stomach and mucosal protective drugs. There are three categories of acid suppressant drugs: (1) antacids and (2) histamine receptor type 2 (H2) antagonists, and (3) proton-pump inhibitors that block gastric acid secretion. “The only mucosal protective drug being used, says Murray, is sucralfate and it is only effective for the glandular lining of the stomach and the duodenum, where ulcers and lesions are less likely to occur.” The H2 antagonists are Murray’s drugs of choice in most cases. “Treatment with H2 antagonists,” he says, “has been successful in resolving the gastric lesions and in resolving the presenting problem. Cimetidine (Tagamet) and ranitidine (Zantac) are the most frequently used, and both inhibit gastric acid secretion in horses.”

Additional Resources:

Blue Ridge Equine, “Gastrogard Versus Ulcergard…” http://www.blueridgeequine.com/gastrogard-versus-ulcergard-protect-your-horse-from-equine-ulcers/

Kentucky Equine Research, “New Thoughts on Gastric Ulcers in Horses,” https://ker.com/equinews/new-thoughts-gastric-ulcers-horses/

Nieto, Jorge, DVM, Ph.D., DACVS, “Diagnosing and Treating Gastric Ulcers in Horses.” UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. https://www2.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/ceh/local_resources/pdfs/pubs-Oct2012-sec.pdf

Succeed Veterinary Center, “Equine Glandular Gastric Ulcer Syndrome,” https://www.succeed-vet.com/education/equine-gi-disease-library/gastritis/eggus/

The Horse, “Gastric Ulcers.” https://thehorse.com/14523/gastric-ulcers/

The Horse, “It’s Enough to Give Him an Ulcer!” https://thehorse.com/151494/its-enough-to-give-him-an-ulcer/

The Horse, “Compounding Study: Know What You’re Getting.” https://thehorse.com/130700/compounding-study-know-what-youre-getting/