Saddle Fit and Jumping Saddles

By Jochen Schleese, CMS, CEE, CSFT

©2016 Saddlefit 4 Life. All Rights Reserved

The art and science of saddle fit has become part of the consciousness of the importance of truly caring for your horse; of really working together with every equine professional who is part of the “circle of influence” around horse and rider. Traditionally however, it has been dressage riders and endurance riders who have been the most concerned with having a properly fitting saddle, because these are the disciplines where it seems to really matter how comfortable the horse (and rider) are – because otherwise performance can be visibly impacted.

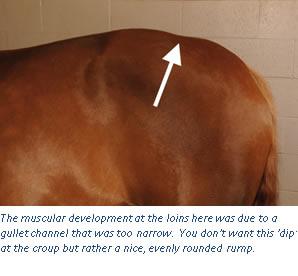

The design of jumping saddles has been primarily dictated by a certain ‘look’ that especially hunters want to achieve; little attention has been paid to a) whether these saddles actually are ‘anatomically correct’ for the rider and b) whether they actually fit the horse. If you look closely at pretty much any jumping saddle, you will discover that they all generally have very narrow gullet channels and non-adjustable panels made of felt or wool. The paradox is that the ‘close contact’ the rider wants to achieve becomes pretty much non-existent after keyhole rubber pads and other saddle pads are added. Very rarely will you find a truly adjustable jumping saddle that can be fitted in the flocking as well as adjusted in the tree width and angle to accommodate the shoulder angle and necessary room all around the withers.

Hunter/jumper saddles are usually placed pretty far forward on the horse’s back – which is good, because you generally do want to sit as close to the withers as possible as this is where the horse’s back ‘swings’ the least – but it is also bad, because often times in achieving this, the treepoints are actually placed on or over the shoulder blade. This will of course impact the horse’s freedom of movement over the shoulders and shorten his stride and ability to actually jump. The next result of this is that instead of allowing the rider a balanced seat, the pommel will be much higher than the cantle – thus the need for pad after pad to bring the back of the saddle up level again. Most riders prefer the jumping saddle to be center-balanced.

Particularly the shape and position of the gullet plate, the stiffest and most stable part of the saddle, needs to accommodate the natural asymmetry (i.e., usually the left shoulder is bigger – higher and further back) in the horse’s anatomy during saddle fitting. Its necessary function cannot be substituted for or eliminated by reflocking, shimming, or the use of other special orthotics in the panel area. Because of the pretty common occurrence of the unevenness at the horse’s shoulders, it will usually be necessary to fit the gullet plate asymmetrically in order to achieve this necessary support equally well on both sides, and allowing the required freedom of movement for both shoulders equally. As a matter of fact, if this crucial piece of saddle fitting is ignored, and a saddle with a symmetrical gullet plate is put on a horse’s back – it will inevitably fall to one side as it is pushed there by the more heavily muscled shoulder (usually the left, twisting the saddle to the right). You will see many instances of pictures of riders from behind sitting on a saddle which seems to have slipped to the right.

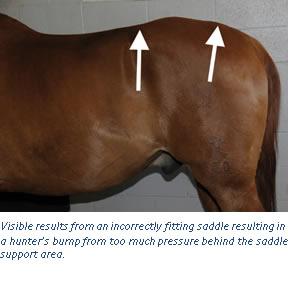

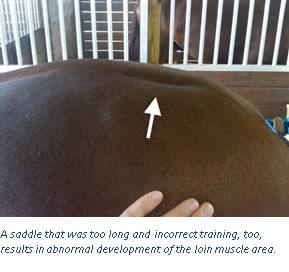

There are many obvious visual manifestations of poor saddle fit – some of them will be deemed ‘behavioral’ issues; some of them are actually physiological. Some of the behaviors that may be experienced and can usually be attributed to poor saddle fit can be directly caused by the saddle impacting some of the reflex points – resulting in ‘negative’ or unwanted behavior. These would include bucking, refusing to jump, stumbling, tripping, or not rounding the back. The so-called ‘hunter’s bump’ or a dip behind the withers (due to severe muscle atrophy) is often seen in hunter/jumpers.

It would seem necessary – especially in hunter/jumpers, where the ability to move freely in order to jump is key – to have a saddle that can be adjusted over the course of the horse’s life; as he matures and changes conformation over the years. Instead, we find remedial fitting practices using more and more shims and pads, or simply replacing saddle after saddle.

We invite the reader to check the fit of their saddle(s) using the 9 point checklist and following along with the YouTube videos at https://www.youtube.com/c/Saddlefit4Life orwww.saddlesforwomen.com. What you learn might surprise you and change your perception of saddle fit!

By Jochen Schleese, CMS, CEE, CSFT

©2016 Saddlefit 4 Life. All Rights Reserved

The art and science of saddle fit has become part of the consciousness of the importance of truly caring for your horse; of really working together with every equine professional who is part of the “circle of influence” around horse and rider. Traditionally however, it has been dressage riders and endurance riders who have been the most concerned with having a properly fitting saddle, because these are the disciplines where it seems to really matter how comfortable the horse (and rider) are – because otherwise performance can be visibly impacted.

The design of jumping saddles has been primarily dictated by a certain ‘look’ that especially hunters want to achieve; little attention has been paid to a) whether these saddles actually are ‘anatomically correct’ for the rider and b) whether they actually fit the horse. If you look closely at pretty much any jumping saddle, you will discover that they all generally have very narrow gullet channels and non-adjustable panels made of felt or wool. The paradox is that the ‘close contact’ the rider wants to achieve becomes pretty much non-existent after keyhole rubber pads and other saddle pads are added. Very rarely will you find a truly adjustable jumping saddle that can be fitted in the flocking as well as adjusted in the tree width and angle to accommodate the shoulder angle and necessary room all around the withers.

Hunter/jumper saddles are usually placed pretty far forward on the horse’s back – which is good, because you generally do want to sit as close to the withers as possible as this is where the horse’s back ‘swings’ the least – but it is also bad, because often times in achieving this, the treepoints are actually placed on or over the shoulder blade. This will of course impact the horse’s freedom of movement over the shoulders and shorten his stride and ability to actually jump. The next result of this is that instead of allowing the rider a balanced seat, the pommel will be much higher than the cantle – thus the need for pad after pad to bring the back of the saddle up level again. Most riders prefer the jumping saddle to be center-balanced.

Particularly the shape and position of the gullet plate, the stiffest and most stable part of the saddle, needs to accommodate the natural asymmetry (i.e., usually the left shoulder is bigger – higher and further back) in the horse’s anatomy during saddle fitting. Its necessary function cannot be substituted for or eliminated by reflocking, shimming, or the use of other special orthotics in the panel area. Because of the pretty common occurrence of the unevenness at the horse’s shoulders, it will usually be necessary to fit the gullet plate asymmetrically in order to achieve this necessary support equally well on both sides, and allowing the required freedom of movement for both shoulders equally. As a matter of fact, if this crucial piece of saddle fitting is ignored, and a saddle with a symmetrical gullet plate is put on a horse’s back – it will inevitably fall to one side as it is pushed there by the more heavily muscled shoulder (usually the left, twisting the saddle to the right). You will see many instances of pictures of riders from behind sitting on a saddle which seems to have slipped to the right.

There are many obvious visual manifestations of poor saddle fit – some of them will be deemed ‘behavioral’ issues; some of them are actually physiological. Some of the behaviors that may be experienced and can usually be attributed to poor saddle fit can be directly caused by the saddle impacting some of the reflex points – resulting in ‘negative’ or unwanted behavior. These would include bucking, refusing to jump, stumbling, tripping, or not rounding the back. The so-called ‘hunter’s bump’ or a dip behind the withers (due to severe muscle atrophy) is often seen in hunter/jumpers.

It would seem necessary – especially in hunter/jumpers, where the ability to move freely in order to jump is key – to have a saddle that can be adjusted over the course of the horse’s life; as he matures and changes conformation over the years. Instead, we find remedial fitting practices using more and more shims and pads, or simply replacing saddle after saddle.

We invite the reader to check the fit of their saddle(s) using the 9 point checklist and following along with the YouTube videos at https://www.youtube.com/c/Saddlefit4Life orwww.saddlesforwomen.com. What you learn might surprise you and change your perception of saddle fit!